What then is this "fourth wave" exciting the bourgeois imagination, and stoking the fires of conspiranoia? They are the new wave of automotive and robotic technologies, the ways of doing things enabled by artificial intelligence and machine learning, the new communicative possibilities opened by the proliferation of social media and, crucially, the potential productivity gains marrying all these together have and (subtext) the boost to profits this entails. The drivers of the new wave of innovation share digitisation in common, but are clustered in three interrelated areas of new technologies: the physical, such as self-driving vehicles, 3D printing, and the emergence (and application) of new materials like graphene and carbon nanotubes; the digital (internet of things, crypto-currencies, on-demand supply and retail); and the biological (gene sequencing, editing, and therapy, precision medicines, organic 3D printing, synthetic biology, neurotechnologies). The only thing holding back these developments, Schwab breathlessly writes, is the (paradoxically) conservative character of innovation cultures. He singles out the tying of innovation to academic career incentives, and the competition among tech firms to poach staff from labs, a zero sum game that closes off the win-win possibility for collaboration. To tackle this he suggests more public/private partnerships under the direction of state led research programmes - something, interestingly, the recently departed Dominic Cummings was quite enthusiastic about.

However, unlike the utopian tone struck by most futurists Schwab notes the disruptive character of these technologies. On the one hand, communicative technologies and 3D printing contain empowering possibilities. The downside for capitalism is deflation. New waves of automation are bound to eat into wage scales, but simultaneously drives the costs of goods down, making consumption cheaper and, at least in theory, less resource intensive and sustainable. Furthermore, Schwab notes productivity, understood here as the rate of economic growth, has shrunk over the last 50 years. Taking the United States as the most developed of developed nations, between 1947 and 1983 annual growth averaged at 2.8%. 2000-07 it had fallen to 2.6%, and between 2007 and 2014 1.3%. If the fourth wave is here, it's not making itself felt according to the traditional measures. Even worse, the impacts of fourth wave technologies is not creating jobs in sufficient numbers to replace those lost/rendered obsolete. With 47% of US jobs at risk of automation, in 2016 only 0.5% of Americans were employed in jobs that did not exist in 2000. Globally, new technologies allow for developed countries to reshore work with new automative processes, but work does not necessarily mean job recreation on a massive scale - this also means the closure of one developmental path taken by countries of the global south, the consequence of which could be economic depression as a key driver of migration patterns. If anything, the fourth wave is a job killer.

The fourth wave also presents states a challenge. The growth and importance of networks for capital accumulation are simultaneously strands of social relationships that can instantiate new communities of interest and generate rival (or dispersed) centres of power. The pace of change also presents democratic checks and scrutiny a challenge - how might a parliament legislate and regulate with development proceeding at rapid velocities? Schwab suggests 'agile' government could meet this challenge, which involves new compacts between the state, business, and our friend 'civil society' to generate dispersed governance. It sounds like Schwab read Hardt and Negri's description of the dispersed state in Empire but rather than finding something repulsive, instead he discovered a model. However, dispersed management can sit quite well with a more authoritarian state.

There's a bit more in the book about the dangers of the network, particularly fake news and the visibilising of disconnects between publics and the politicians (and others) who mske decisions on their behalf. Schwab also forecasts new inequalities of an ontological character between those adapting to the new way of the world and those who might resist them, exacerbated by existing generational divides. How to avoid the downsides? As you might expect from the head of the World Economic Forum, the suggestions are woolly and only realy suitable for management seminars on, um, the fourth industrial revolution. We must avoid "compartmentalised thinking" and think collaboration and ecosystem! Okay. Second, more positive thinking is needed, including the elaboration of a new set of ethics to guide development in the new age. And lastly, the world has to restructure its economies to make the most of the benefits the fourth wave bring, but rather than IMF-style "structural adjustments" this should be a dialogic, democratic process - something, interestingly enough, conspiracy theoroid commentary on Schwab's work tends to neglect.

Does this sound like an exciting book to you? Probably not. Especially when similar material has been covered in a more satisfying and sophisticated manner by leftist authors. Schwab's book, of course, isn't meant to be a treatise: it was written as a quick bourgie guide to the 21st century for busy executives on the go, and so perhaps might be forgiven a little bit for being economic with the structural actualité. The truth of the matter is while all these technologies are being developed, there is little profitable use (yet) for them. What's the point in splashing out on fancy software or new automative systems with significant upfront costs during an economic depression in which millions of people are out of work? Labour, and relatively cheap labour is in plentiful supply right across the developed nations. Shutting them out of employment without an appreciable bump in profits above the average profit rate, and with the outlay means the "revolution" at work is delayed and is rolled out around the edges. For instance, the homeworking enabled by Zoom, Teams, and the like doesn't change much, despite the boosterism of the hypesters.

Yet a revolution delayed is not necessarily a revolution thwarted. As Ernest Mandel notes in Late Capitalism, previous waves of technological innovation that deliver surplus profits, at least initially before a new equilibria around a reset average rate of profit, can take decades to unfold before stagnation sets in. We have economic stagnation already, the introduction of new technologies has led to new monopolies (hello Facebook, Amazon), but as yet no system-wide surge in productivity - something Coronavirus and its consequences are likely to retard further as the incentives aren't present or rewarding enough for properly teching up. Perhaps this is something Schwab addresses in his most recent book on the, ahem, Great Reset after the pandemic. Meanwhile, our job isn't a passive one. Technologies are not neutral, they are always stamped by the societies that make them. As capitalist dynamics are pregnant with authoritarian and liberatory possibilities, so its technologies tend to be so too. We have to push public understanding about cutting edge developments, intervene vigorously in debates about the uses (and abuses) of science, and make the case that the full exploration and flowering of these potentials are only possible in a society in which human beings are valued and free. Perhaps the fourth industrial revolution needs the company of a revolution of an allied, but different character for the good life it offers to be fully realised.

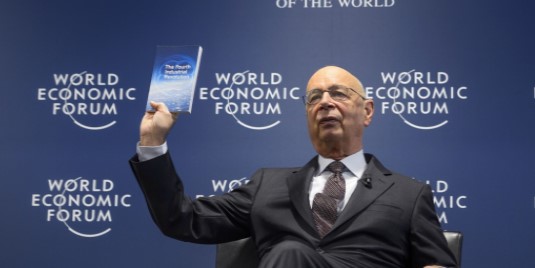

Image Credit

3 comments:

«the introduction of new technologies has led to new monopolies (hello Facebook, Amazon), but as yet no system-wide surge in productivity»

My usual hypothesis here: that what has delivered so far 90% of productivity gains has been not new technologies, but new fuels, cheaper and at the same time more energy dense, first the switch from vegetables/wood to coal, and then from coal to oil.

Note also that the business and property rentier elites don't *need* higher productivity, they already have lives of stunning, extraordinary, luxury, with 100m yachts, palaces with hundreds of rooms, etc. etc.

The new technologies *might* increase a bit productivity and profits, but also something else matters: a common mistake is to assume that business and property owners care only about profits, but they also care as much or more about control and power, and human workers are hard to control. A lot of the newer technologies are about replacing uppity human resources with more docile alternatives.

https://dilbert.com/strip/2018-07-03

https://dilbert.com/strip/1994-04-01

https://dilbert.com/strip/2008-01-26

Who needs productivity increases when you can just print money to keep the hierarchies intact. Keep that printed money to just he elites and you don't have to worry about inflation. This was the lesson of 2008. Some call it neo Feudalism because they think capitalism is somehow wonderful and been corrupted but it is actually just plain old capitalism.

“making consumption cheaper and, at least in theory, less resource intensive and sustainable.”

You really are going to have to explain this one! Greater productivity always ends up with more resources being used up, not less. In fact the beauty/horror of the technology is that it can produce more in one hour than previous technologies, which is why it’s cheaper.

The only way to use up fewer resources is to literally offer less. Like when the confectionery companies reduce the weight of their chocolate bars but sell it at the same price. This isn’t the result of some technological breakthrough but is simply the result of a hustle, and we the consumers are the mark.

So, if the technology of the future uses up fewer resources we are being hustled yet again.

One reason for the lack of increase in productivity is because much of the computer technology does not provide more output but simply expands the ‘consumer’ experience. So supermarkets can offer checkouts without staff, but they also have checkouts with checkout staff and usually someone to help customers work out the non checkout bits. It’s a retail boom, it expands analytics for companies, but it doesn’t necessarily replace human labour on mass, at least not the recent developments.

The virus has probably helped speed things along in regards of pushing out the old way of doing things and heralding in the new and this being capitalism, lots and lots of misery will entail as a result.

Still at least this guy is not that nauseating tosser Paul Mason, we should be thankful for small mercies.

«Some call it neo Feudalism because they think capitalism is somehow wonderful and been corrupted but it is actually just plain old capitalism.»

A lot of it is actually neo feudalism, based on rentierism and personal relationships, where for example inheritance becomes a big determinant of one's life.

«Greater productivity always ends up with more resources being used up, not less.»

In case people want to check this the technical term is "Jevons paradox", but it only applies to some super-useful resources like energy, that effectively add to disposable income.

Post a Comment