Looking at the field of selections, of which only two out of 100 have been won by "the left", Maguire writes of a Labour left in despair. The Socialist Campaign Group, who've always been less than the sum of its parts are "terrified", worried that they'll be deselected for being close to Stop the War. One anonymous source opines to Maguire that there won't be a single left-wing idea left on the table by the time Keir Starmer is done. But amid the gloom, the slightest glimmer of hope! Another anonymous mouthpiece loyal to the Starmer project reckoned all their work driving out the left could be undone if a major union swings to the left. I.e. Unison or GMB. Or, assuming a small majority, the left will be able to extract a series of concessions from a Starmer government. As if implementing policies that make life better is a bad thing. The not so subtle argument pushed by Maguire being that Starmer should have purged the SCG from parliamentary party when he had the chance. Now all of them are on "best behaviour", moving now would come with political costs attached. Such as galvanising the remains of the left activist base, prodding trade unions to do more than issue meek protests, or failing to capitalise on the latest Tory calamity.

The right worrying about the left now sounds absurd now, but it does represent an unease embedded in the character of Labourism itself. As a politics that emerged from the struggles of the working class two centuries ago, it replicates and, in practice, reproduces the split in capitalism between employer and state, between economics and politics. As a result, the varieties of Labourism that have issued from this have ranged from conservative to accommodating, from reform-minded to the radical. And their respective periods of dominance in the party roughly correspond with the advance and retreat of the labour movement. For instance, the 1945 Labour government was the beneficiary of an upsurge of working class confidence and radicalism during the war. 70 years later, Corbyn's victory in the leadership contest condensed the politicisation of millions which reflected their experience of life and work, and an establishment politics that didn't speak to them at all. New Labour, on the other hand, was a product of labour movement defeat. With the trade unions in serious retreat after the 1980s, combined with the decomposition/recomposition of the working class, the increasing privatisation of social life, and the end of Stalinism in Eastern Europe and Russia, the collapse of organisation and consciousness made the conditions for Blairism's centrist and authoritarian politics possible in the Labour Party.

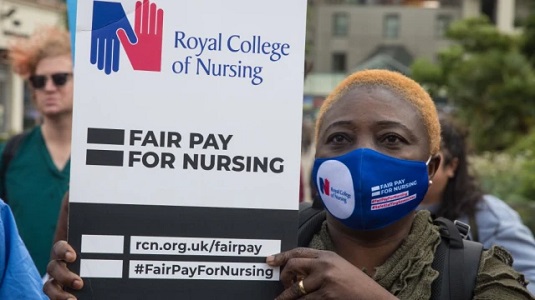

Because of Labour's link to the labour movement, the right's victory over the left can never be total and permanent. The relationship is simultaneously a source of stability and uncertainty. In terms of a cadre of activists and ready money, friendly trade union leaders can help steady the ship and did, in the past, police the industrial activism of their members. Which is what we've historically seen from right wing trade unionists. But if the wider trade union movement is active and millions of workers are moving into industrial action, the possibility of that politics making its way into the Labour Party is a live one.

Which is where we are now. The comparison is often made between Starmerism and Blairism, and there are some similarities. The language of modernisation and authoritarianism being the most obvious. But they face different circumstances. Tony Blair presided over the aftermath of labour movement defeat, and not only had it not recovered by the time he left office New Labour policies actively stymied it. If there is a parallel for Starmer, it's the Harold Wilson/Jim Callaghan governments in the sense that they faced a rising tide of workers' struggle while trying to keep a lid on it. Obviously, what is happening now is at a lower pitch of intensity and isn't drawing in as many people, but for the right wingers who have Starmer's ear it's enough to feel the tug of its coalescing political gravity. Corbynism was an unwelcome surprise for them that no one saw coming, including the Labour left itself. But industrial unrest has prefaced and fuelled radicalism in the past, which is a fact not even selective readings of history can deny. Therefore the concern, even though the left in Labour are at a low ebb, with the possibility of a return. But this time rooted in a movement outside of the party and carrying institutional heft within it.

Despite the right wing anxieties and where it's coming from, I don't think the right wing night terrors are about to materialise. Even though there have been some stunning victories, especially with the RMT's victorious result over Network Rail. For one, Starmer has made it clear that Labour is no home for radical or socialist politics, and he's been marginal to irrelevant in the industrial disputes and struggles of the last couple of years. And when he's in government and the inevitable attacks on workers come, it's doubly unlikely they will move into the party in response. It didn't happen in the Blair/Brown years, after all. In fact, it wasn't until well after they had both departed from office that a left anti-Blairist politics coalesced around Corbyn. In other words, we're looking at the medium term. Instead, with the likelihood of the Tories taking a sharp right turn following their coming defeat, other alternatives to Labour are set to benefit. The Liberal Democrats? Possibly. They did well out of the Blair years. The Greens? Almost certainly, especially as the climate crisis really starts biting. The SNP? Provided their current difficulties don't prove fatal, they cannot be discounted given their position of strength vis a vis Scottish Labour. This is all outside of Labour, but 10 years down the line after Starmer has left office something like the Bennite or Corbynite surges cannot be ruled out. If an opportunity opens and it hasn't found expression elsewhere, then Labour could again become the key political battleground.