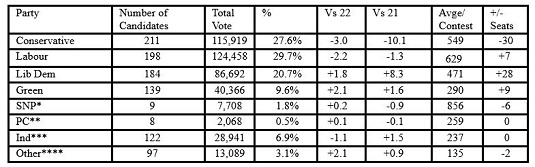

This month saw 20,444 votes cast in 14 local authority contests. All percentages are rounded to the nearest single decimal place. Only three council seats changed hands. For comparison with November's results, see here.

Party

|

Number of Candidates

|

Total Vote

|

%

|

+/- Nov

|

+/- Dec 22

|

Avge/

Contest

|

+/-

Seats

|

Conservative

|

15

| 7,035

|

34.4%

| +15.0

|

+3.2

|

469

|

-3

|

Labour

|

14

| 3,219

|

15.7%

| -11.7

|

-12.8

| 230

|

0

|

Lib Dem

|

14

| 8,363

|

40.9%

| +22.7

|

+27.5

|

597

|

+3

|

Green

|

11

| 1,331

|

6.5%

| -4.0

|

-0.5

|

121

|

0

|

SNP*

|

0

|

|

| |

|

|

0

|

PC**

|

0

|

|

|

|

|

|

0

|

Ind***

|

4

| 460

|

2.3%

|

-12.4

|

-8.9

|

114

|

0

|

Other****

|

1

|

36

|

0.2%

| -5.9

|

-0.3

|

36

|

0

|

* There were no by-elections in Scotland

** There was one by-election in Wales

*** There was one Independent clash

**** Others this month consisted solely of Reform (36)

There isn't a great deal to say about this month's crop of contests. As noted in the November write up, December was destined to be a Tory/Liberal Democrat clash and so it proved. Labour came in a distant third and the Lib Dems have triumphed with a three seat haul and, if memory serves, their highest share of the popular vote ever. Does it mean much? Not really. The results are reiterating the re-emergence of the Lib Dems as the protest party of choice for disgruntled Tory voters. Whether this carries through into a general election scenario is something we will find out next year.

For once, January is offering an embarrassment of riches where the number of contests are concerned. Normally the slowest month on the by-election calendar, we can look forward to 11 of them.

7th December

Bromley, Hayes & Coney Hall, Con hold

Denbighshire, Rhyl South West, Lab hold

Hertfordshire, Harpenden Rural, LDem gain from Con

North Norfolk, Briston, LDem hold

St Albans, Sandridge & Wheathampstead, LDem hold

14th December

Cotswold, Lechlade, Kempsford & Fairford South, LDem hold

North Kesteven, Billinghay Rural, LDem gain from Con

Rugby, Dunsmore, LDem gain from Con, Con hold

Swale, Abbey, LDem hold

Three Rivers, Chorleywood South & Maple Cross, LDem hold

Warwickshire, Dunsmore & Leam Valley, Con hold

21st December

Blaby, Glen Parva, LDem hold

Isle of Wight, Ventnor & St Lawrence, Con hold

Leicestershire, Blaby & Glen Parva, LDem hold

Image Credit