In Mission, humans several centuries hence are investigating Mesklin. It's a poisonous, frigid world that gets up to a balmy -50C in the summer. If that wasn't bad enough, the planet's gravity is punishingly uncomfortable to outright fatal for flimsy earthlings. Because the world spins so rapidly, it's tolerable near to and on the equator where gravity is only three times that of Earth. But towards the poles it ramps up to over 600Gs, which would turn us into bloody puddles. What happens if the exploration of this world lands an advanced expensive probe near one of the poles, but its gravity-nullifying engines fail and it remains there marooned? How to get it back? This is the task our on-site boffins have to accomplish.

Luckily, Mesklin is inhabited by intelligent life forms. The imaginatively-named Mesklinites are roughly at a pre-gunpowder level of technology, and are scattered across the southern hemisphere in small states. They also think their world, which is an oblate spheroid thanks due to its rapid spin (a day is approximately 18 minutes long), is bowl-shaped. The equator represents the edge of what is known and, presumably, no one has crossed it nor has anyone sallied down from the north. It also happens that Charles Lackland, the member of the planetary investigation team that volunteered to reside on the surface, has struck up a friendship with Barlennan, a ship's captain, explorer, and trader. He handily brings a crew to the party. The Mesklinites are well adapted to their world too. They're foot long centipede analogues with their equivalent of opposable thumbs. A bargain is struck between the two: retrieve or fix the probe and riches will be his. Barlennan receives four radios and regular weather reports in this fetch quest. They have to overcome environmental hazards, hostile wildlife, spear chucking tribes, supercilious bureaucrats, as well as teaching pre-industrial sailors how to fix a rocket.

Like Clarke's A Fall of Moondust, Clement's book doesn't have a fantastic reputation these days - especially among booktubers for whom whizz bang is largely king. Clement's characterisation isn't fantastic, it's low on action, and there are info dumps - albeit of the physical sciences sort and not the vibrant lore that accompanies most genre fiction. But again, like the Clarke, Mission exceeded my expectations. There are only really three, maybe four (if you count the planet), characters and they do the job. Barlennan is shown to be a wily operator with the gift of the gab and an ability to make the most of whatever situation Clement puts him in, The rapport he has with Lakeland is believable, even if it the captain has ulterior motives. Their relationship works to move the plot along which, again, is about solving a seemingly intractable problem. There is no superfluity, and we skip around Gravity's equator in very little time.

Perhaps the "boring" verdict lies in its being emblematic of a zeitgeist that has long passed, and profitably lampooned by the Fall Out series of video games and TV series: the 1950s flavoured hopes in science. When the Mesklinites finally reach the probe Barlennan demands, as the price for his further cooperation, the technological know how for guns, rockets, radio, and so on. Instead Lakeland and co. teach him the scientific method, which presumably would make Barlennan very rich upon his return home and (hopefully) improve the overall lot of his people. This speaks of the American character of US SF of the period. For the Clarke, proceedings were dutiful, unshowy. It was just professionals doing their job. Here the challenges are met by mustering Barlennan's faceless crew. His first mate, Dondragmer, has a knack for conjuring up schemes for getting them out of their scrapes but whatever the challenge, the spotlight is on them. They're the individuals who stand out and front the labour of others. In Moondust, the collective effort saved the Selene and that was that. In Gravity, it's these two who are the heroes, they're the ones that get centred, and are going to be the reapers of the rewards. This makes it as American as Clarke's adventures on the Moon locate it as British.

But there's perhaps a gentle warning in Clement's novel. Science can do wonderful things - it can transport humans 11 light years to another world, for one. But even here there are limits. No matter the expertise and the systems we design to support them, things can always go wrong. And with the Mesklinites, despite their pre-industrial level of development they know their world better than our star-bestriding descendents do. Rather than an uncritical celebration of postwar technocracy, there's a note here telling us not to become arrogant, not to presume to know everything, a hesitation injuncting us to take care. Only fools, or people set on losing an expensive space probe, would ignore common sense and local knowledge.

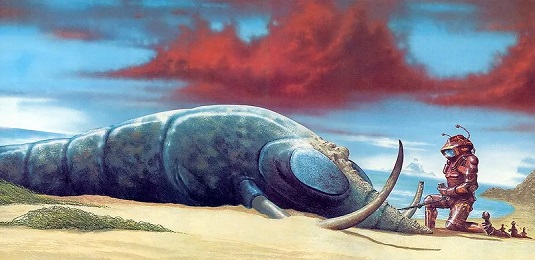

Image Credit

1 comment:

If you fancy a more whiz-bang take on the super high gravity environment theme, try Raft by Stephen Baxter. Set in a high-gravity universe where the stranded humans can walk on dead stars, because nothing massive enough to exert an immediately lethal gravitational pull can exist without collapsing to a black hole. Be warned of some serious ick and credulity-testing Deus Ex Machinae in the midsection - but the first and third acts are pretty good (at least as far as I can remember) and it's a wild piece of world-building.

Post a Comment