Video game history since then, when looked at askance, could be described as a series of encounters between these principles. "Immersive" elements from role playing and adventure games invaded arcade conversions, particularly on Nintendo and Sega machines. Fancy a spin on Super Hang-On and Super Monaco GP? Here, have a bolt-on career mode to give a quote shallow arcade experience some depth and longevity. It worked in reverse too. The Legend of Zelda is widely-credited with popularising the action RPG genre, at least outside of Europe. The mutual to-ing and fro-ing of tanks on each others' lawns gathered pace with hardware capable of rendering 3D environments. Action and immersion were less antipodes, and more bezzy mates. One could play an action experience like Tomb Raider, but simultaneously get lost in its intricate puzzling and game world. The story-telling one used to associate with cerebral games bust out of "high gaming" and established itself as standard to action-oriented product.

The Killzone series typifies the change mainstream action games have undergone. Three generations of Playstation (the 2, 3 and 4) have been graced by four titles. In case you don't know, Killzone is a first person shooter, and it's you vs the space Nazis. In the not-too-distant future the human race have colonised two worlds around Alpha Centauri. Vekta is a blue/green paradise very much like our pearl of a planet. Helghan, by contrast, is a hell hole. There is, as you might expect, a detailed back story, but to cut to the chase the Helghast have a grievance, and as a Hobbesian dystopia with heavy 3rd Reich overtones, it wants its lebensraum back.

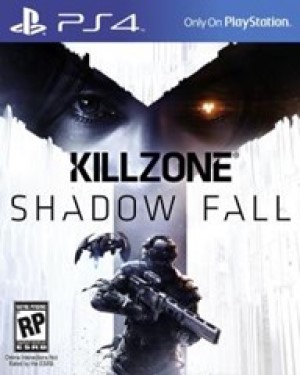

Killzone on the PS2 sees the Helghast invade our sleepy, liberal-loving Vekta and it's up to you to beat them back. In the second game's outing early on in the PS3's life you are part of Vekta's counter-invasion of Helghan. It's down to you to hunt down and capture the crazed half-Hitler, half-Mussolini Helghast chancellor. The third game, also on PS3, is about your escape from Helghan and your efforts to prevent the deployment of a super weapon. The game concludes with a radioactive chain reaction that sweeps Helghan's surface, laying waste to the population lying in its path. Is the threat finally over? Well, no. There would be no Killzone: Shadow Fall (KSF) available for the PS4's release otherwise.

KSF is definitely a superlative product. As you would expect from a next generation system, the leap in performance is palpable but not as obvious as preceding console generations. To get a sense of it, if you take a cut scene from a PS3 or Xbox 360 game, the PS4's performance is akin to playing them. As such it's one of the most beautiful games out there.

This time Vekta is the scene of much of the action. Following the last game, which rendered Helghan uninhabitable, the survivors are granted land on the lush, green planet they were driven from in the first place. In fact, half of Vekta's hemisphere is handed over to the former enemy. Three decades on Vektans and Helghast lead an uneasy co-existence either side of a globe straddling wall. The Cold War is in, David Hasselhoff rocking Looking for Freedom atop the wall definitely is not. The game casts you as Lucas Kellan, a so-called Shadow Marshall who is tasked with all kinds of stealthy missions on the other side. The plot proper kicks in about a third of the way through which tasks you with tracking down the leader of the 'Black Hand', an underground Helghast terror group responsible for bombings, shootings and attacks against Vektan civilian targets. And it gets increasingly murky from there.

KSF is interesting because it self-conciously plays across the two levels of video game analysis established here. Like the bulk of modern video games, and especially first-person shooters, the backdrop and in-game narrative are open to what you might call "standard" ideology critique. In this case it's about protecting Vekta, which resembles the clean, hypermodern USA/West of science fictional imaginations against a scary Other. In this case, polluting, war-crazed, racist genocidal Nazis who go into combat wearing coal scuttle helmets and glowing gas masks. It opposes the liberal, tolerant values of Vekta with the totalitarian madness of the Helghast. It's straight forward goodies and baddies. Humanity vs The Covenant in Halo. Humanity vs The Hybrids in Resistance: Fall of Man. The yanks (and British!) vs (ultra nationalist) Russians in Call of Duty. And humans vs the Locust in Gears of War. The Alliance vs The Reapers in Mass Effect. It's very black and white, very straight forward.

KSF however pulls a neat narrative trick that puts some distance between these standard storytelling ploys. The franchise story line is founded on an ambiguity in the first place. As rancid and as fascistic the Helghast became, they are the ultimate blowback - the result of a planet wide eviction and subsequent exile to a barely-habitable rock. You forget that during the course of the first three games, bent as they are on genocide and other dark things. KSF on the other hand finds out that Vekta are up to some very murky things. Under the protection of Earth alliance military, the ISA, it turns out has been employing one Dr Hillary Massar. In true Mengele fashion, she is experimenting on live Helghast captives to produce a bioweapon that will target their biology specifically. Of course, she ends up getting lifted by the Helghast who quite fancy getting their hands on her research, and so a major plot point turns on trying to recapture Massar and repatriate her work to the Vektan cause. Also, for the first time, in the covert missions on the other side of the world we are introduced to Helghast civilians for the first time. As you might expect in a tyranny overseen by a fascist aristocracy, the people you meet are poor, downtrodden, and clearly in need of a meal. They live in corrugated shacks wedged between glowing, gothic-looking skyscrapers and their sense of despair is palpable. At one point you have the choice of preventing a man from blowing his head off while his anxious wife looks on, sobbing. Are the Helghast you've spent three previous games shooting at that different from us? It would seem not, which makes the plan to wage germ warfare on them all the more obscene - even if their regime is appalling.

Ah, the regime. This is where things get interesting. One of your repeat antagonists is Tyran, the mastermind behind the Helghast terror cells on your side of the wall. You end up in a few scraps with him. Like all good villains, he can't resist taunting you as you make your way to the place of battle. But instead of trash talking, he goes off on a sub-political lecture about the Helghast - how they are a "worthy people" because they battled with Helghan's poisonous environment to build a mighty military power, and how Vektans are soft and aimless because they don't believe in anything. They might have affluence and liberty, but they lack loyalty to something larger than themselves. Which is why, of course, the Helghast will eventually win. It makes you wonder if this is a comment on US society and those who are arrayed against it.

Nothing wrong with a little bit of ambiguity. But it's right at the end where KSF performs its cleverest narrative trick. While you're approaching Stahl's hideout (Stahl being the bad guy from the previous game, think Sting/Goebbels), his voice rasps out of the speaker informing you that Vektans are selfish, fear one another, and that their sole motivation is greed. A rhetorical flourish before he's dispatched into the night? Or is he speaking directly to you, the player, about your motivations and your culture. Why are you playing this game? Because you like overthrowing digital dictators or simply fancied a blast with a state-of-the-art game on a state-of-the-art system? You who throughout the game and its predecessors have merely followed orders - both of non-player characters and the game's logic. And the ambiguity returns in the final seconds of the game with a vengeance that puts into question everything you have done in KSF, including why you've sat there for hours battling through the 24th century Wehrmacht.

Plenty of games throw twists and ambiguous touches at you, but few like Shadow Fall call into question the reasons why you're playing the game. At least on my reading. If this narrative ploy that uses a well-crafted game universe to reach out to the 'meta-level' of gaming culture is going to be used more often, then the new generation of video games promises some very interesting and potentially critical product that goes beyond tired cynicism and overblown satire.

6 comments:

I'm looking forward to my post-crimbo ps4 but not convinced as yet by the games... thinking of BF4 for multiplayer but i suspect we will have to wait a year or so before we see what the PS4 can really do... I'm not convinced by FPS without multiplayer because there is always something a bit too AI about the AI... However seen good reviews for the new Fifa, which I've never played before...

actually, it might be a much more interesting experience if, right at the beginning of the game, a character in the game asked those "big" questions about why are you here and what do you think you're going to accomplish, and then, at the end of the game, another character could ask you if it was all worth it, and whether the experience has changed you and just who do you think you are anyway? but then, how could you go about structuring the game so that it kept changing according to whatever (provisional) answer you came up with.

i don't disagree with you that video games on some level entail a kind of training and some "psycho-physical" or "subject-creating" discipline, but, at this point in time, is that necessarily connected to say, the world of work? if it is, then what does that say about our education system? or are we just being "trained" to keep on playing the game?

according to your description of the situation in this particular game, you can't help organize a rebellion among the downtrodden helghastians against their fascist overlords. too bad, because that would actually give a more political solution to the whole thing. but that seems to be the problem with video games in general--you can't change the rules of the game and still continue to play.

I quite fancy a PS4 for the sake of having one. But modern 3D games make me feel woozy, so I might stick with my old Nintendos and Segas after all.

First anon - I think video games for the last 30 years have been creating a certain set of dispositions that are particularly suited for 'hegemonic' forms of work - object-oriented activity; patient, sedentary work in front of displays; the heightened sense of responsibility for what plays out on the screen (providing the controls are tight enough!), and so on. Tbh this needs a lot more working through - these are just some sketchy thoughts.

"the heightened sense of responsibility for what plays out on the screen." so it's essentially training for middle management. or i guess if you're in your 40s and still playing computer games, you're just polishing up a skill set you've already acquired.

but i have two more questions.

1. to what extent is this kind of immersive role-playing activity itself a kind of performance? and if it is, what are the criteria by which its judged? is it more athletic or is there an emerging esthetic here? and is this too undergoing a kind of professionalization?

2. so what happened 30 years ago? the main thing i can think of is the destruction of a fordist strategy of accumulation with the subsequent breakup of mass culture and its replacement by neo-liberalism and the rise of niche markets and a fundamental change in the work environment. i don't think one can ascribe the growing obsession with gaming merely to the sudden accessibility of a new technology, i.e. the home computer. by the way, 40 years ago, let's say in the late 60s or early 70s, i don't think a lot of men would have been caught dead playing games, unless it was gambling. so what does that say?

p.s. anon one and anon two are the same person: les

Post a Comment