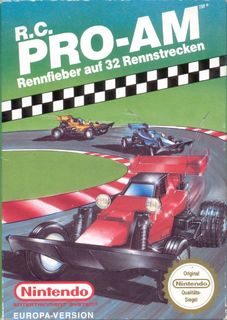

Unlike virtually every other racer from the time, RC Pro-Am adopted a peculiar isometric perspective, which was something of a signature trick of the game's developers, Rare. For those not familiar with the NES but have fond memories of the ZX Spectrum, Rare started out life as Ultimate: Play the Game and made their mark with stunning and, at the time, landmark titles like Jet Pac, Knightlore and Alien 8. The perspective pioneered in the latter titles served Rare well as NES developers, as it was returned to in their most memorable 8-bit outings - Cobra Triangle and the surreal Snake, Rattle and Roll. RC Pro-Am marked the moment Rare had a handle on the hardware and could turn in a virtuoso programming performance without sacrificing the truly crucial ingredient - gameplay.

The game itself is quite a simple affair. You operate a red radio controlled car and race three other computer-controlled opponents around 24 tracks. As you bomb around you can pick up new tyres, new engines, and turbo acceleration that give the car permanent upgrades from race to race. Also laying about are missiles and bombs you can fire at your opponents, as well as roll bars that prevent your car from disintegrating when it crashes, and temporary speed boosts. But there are hazards aplenty from annoying puddles and rainclouds that sap your speed, to oil slicks and retractable walls. The game therefore is a challenge and once you've mastered it, there's always the high scores to amass.

RC Pro-Am was extremely well-received in the video game press and sold very well in North America. But, again, this is an example of the type of game that is very difficult to write about. What you see literally is what you get. Trying to read late 80s British cultural anxiety into 8-bit radio controlled cars is stretching it somewhat, and as revolutionary Rare were, class warriors they were not. Chances are the choice of red for the player's car was not political. I suppose you could say cultural mores and ideology here are curled up in the racing format and the fact you have to not come last to progress to the next race reproduces hegemonic values, but that's as banal a point that could be made about the game. Therefore, for a game of this character which is utterly intense, absorbing and, for want of a better phrase, as "pure" a no-frills gaming experience a video game can be, an ideology critique has to step back from the resistant properties of the game itself and consider it in a wider context.

The NES was particularly successful in Japan and North America because the best games developed for it were genre-defining and fun to play. This is where Adorno's critique of the culture industry comes in. Video games in the NES era more than any other contemporary medium inculcated, disciplined and pacified (mainly young) audiences. While the physical act of watching a film or reading a book is passive, as cultural artefacts there is always a certain openness. Significance of characters can be disputed, questions can be asked about symbolism, and opinions formed about whether it was any good. Video gaming was and is different. While the player can overlay the onscreen action with their own fantasies and narrative, to progress they have to negotiate the mechanics of the game. To move through the game toward completion, memorisation and strategy come into play and the player's body is disciplined by the need to develop the necessary reflexes. Enjoyment of a game like RC Pro Am comes from learning the game, surrendering to one-more-turn syndrome and, once it has been mastered, leisurely bombing around the tracks to get 24 straight wins and/or beating your previous best.

This is a more physical and, perhaps, mentally demanding activity than traditional media. But from a culture industry perspective, it is at the same time more stupefying. It locks into a range of commodified cultural practices common in advanced capitalist societies that offers experiences that ameliorate the myriad social tensions thrown up by everyday life. Video games are safe but tightly-circumscribed outlets for frustration, anger, and the exercise of personal agency. And the loading tray of the NES - and the cartridge slots of its contemporaries - were gaping maws. To get the full value out of your console, you had to buy or rent more games. And of course, if you're busy with RC Pro-Am you're unlikely to find the time to dip into Negative Dialectics. But such is the pernicious character of the culture industry. Conformity is fun. Rebellion is too much like hard work.

2 comments:

I could not, for the life of me, get past a few levels. You had to be near perfect to get past a certain point and I couldn't pull it off. Fun game though, still worth playing every now and again.

It's right bloody tricky. I have got up to level 24 but that's it for me. Usually the game spanks my backside well before that.

Very different to their other NES racer, Super Off Road. Though that being a licensed conversion probably explains why it's super easy - if you've got the patience to sit through all 99 levels.

Post a Comment