Keith Roberts produced six interlinked stories set in a stunted 20th century Britain under the heel of the church. An assassin's bullet struck down Elizabeth I on the eve of the Spanish Armada, with the consequence that the invasion was successful and Protestantism was crushed. The country becomes an unhappy satellite of Rome, Britannia never rules the waves, and the industrial revolution unfolds at a snail's pace. The heavy hand of the papacy weighs on technological development, so in Roberts's 1968 there is no television or radio. The internal combustion engine is in development hell, waiting for its sanction by papal bull. There are no railways, with commerce between cities centring on chugging steam wagons. A dependency on horseback remains. Bandits and dangerous wild animals roam the countryside as smugglers plough the waters. Communication across distances is only possible via chains of mechanical towers under control of the secretive and fiercely independent signallers' guild. As our 20th century compressed time and space and sped everything up, history in the world of Pavane is an unhurried crawl.

Unlike most adventures in other timelines, the book is not a dramatic imagining of hero characters triumphing over the adversities and absurdities of an unfamiliar setting. Instead it deals with the small and how, over a couple of generations, these feed into great events. We get stories of the everyday, the mundane, and the seemingly inconsequential. The one constant is the Dorset environs. Crashing seas and cliff edges, howling winds and bleak heathlands, the clouds roil and billow as the landscape husbands the sluggish and harsh lives of those who survive there. This is a world of superstition and faeries where place is inseparable from the old gods and spirits. Dream and illusion is their favoured manner of manifestation, while the omnipresent Church enforces its divine teaching by the materiality of cannon, soldiery, and the torture chamber. There is a plot of sorts, but it rests lightly on Roberts's canvas. This Britain comes alive in brush strokes, of showing rather than telling.

In later years, Roberts described himself as an anti-communist and a conservative, which was somewhat at odds with the new wave milieu he was a central contributor to. But unlike other writers, the conservatism in Pavane is barely perceptible. It whispers its presence in the privileging of the quiet wisdom of everyone who resides in his Dorset, of a semi-mystical spirit that unites (rural) worker, haulier, signaller, and aristocrat. One nation in one county, you might say. More broadly, Pavane does not read like anti-Catholic polemic in the unionist "no popery!" tradition. Rather, the Church here is a synonym for totalitarianism. It is (theologically) internationalist, indifferent to the peculiarities of its English subjects as long as they don't cause any trouble, pay lip service to doctrine, and fulfils the pope's quotas for foodstuffs and manufactories. This is justified by dogma founded on abstract principles.

Pavane is also Roberts's meditation on the ultimate futility of his politics. Conservatism is congenitally dishonest because it presents the particular, monied interest as the universal interest. But it's also fundamentally pessimistic. Conservatism knows its efforts to preserve what it values are doomed, that the better yesterdays it imagines (or, to be more accurate, invents) are doomed never to recur. While for Roberts the Church Militant is his bogey and Soviet surrogate, it also works as the location for working through conservative anxieties. Based on traditional authority in Max Weber's sense, its ecclesiastical grip cannot halt the flow of history indefinitely. Corfe Gate, Roberts's final story follows the eruption of open defiance and insurgency, enabled by forbidden technologies that work around the sanction of excommunication, and the concluding Coda chronicles the break out of modernity as the papacy crumbles before the hammer blows of revolution. For all its vast apparatus of repression and the chilling effect of its theology, this authoritarian conservative institution could not stymie the flows of history forever. A realisation that might make a commitment to a quieter, more modest everyday conservatism a fruitless exercise, but also the only conservatism that is palatable given the excesses of Pavane's imagined Catholicism.

Because of its pacing, light plotting, and eschewing of the thrills and spills of contemporary SF, Pavane is not for everyone. Those expecting something of that stripe, or even in the ballpark of A Canticle for Leibowitz might wonder what the fuss is about. But readers who appreciate literary fiction and enjoy the flow and beauty of evocative prose will encounter an exceptional work. Not just one of the best SF novels, but a novel of the first rank that deserves canonisation among the English greats.

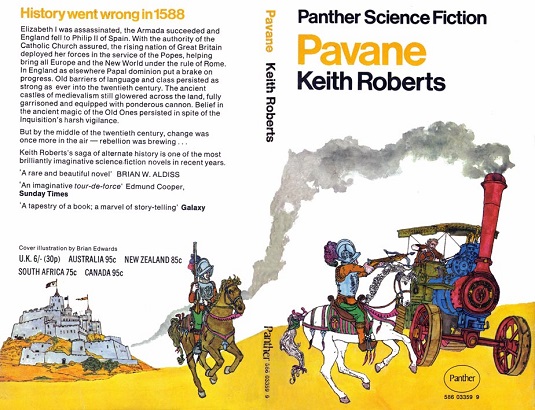

Image Credit

2 comments:

Alternate or alternative history?

Glad to see a lovely review of grumpy Keith’s best book. I agree that it’s one of the greatest SF novels and shamefully ignored.

Post a Comment