Or did Corbyn not save the Labour Party? Well, according to some responses to this tweet, that is the case. The learned Professor Colin Talbot says comparing Labour favourably to the misery of the SPD is "simplistic nonsense" because, um, First Past the Post encourages "big, broad church parties". The implication being that the 2017 general election is merely the natural expression of the electoral system we use, so nothing to see here. The second claim he makes is that if Corbyn is an explanation for why Labour out-performed expectations, then May is equally responsible for the otherwise impressive number of voters who supported the Tories. Well, yes. Here then we have an opportunity to revisit the idea of PASOKification, what's happened to British politics, polarisation, and the empiricism that too often passes for the analysis of politics.

The PASOKification thesis is quite simple. As parties, particularly social democratic and labour parties, pursue policies that are detrimental to their coalition of voters so the tendency for them to collapse increases. This is not a disembodied process, an abstraction sitting above the comings and goings of politics and manifesting willy-nilly, but an outcome of a number of things. Chief among them is the acceptance of a neoliberal programme with New Labour, of course, providing the paradigmatic example. During its terms of office, and despite refurbishing and renewing public services, it politically demobilised its constituency. As the political arm of the labour movement and the party of wage earners, the implementation of market and business-friendly policy did nothing to enhance the collective political strength of its support. Trade union membership continued plunging along with the party membership and the party's vote, alienating many of its (former) voters in the process. Had instead it implemented greater collective rights at work, listened to its membership more and not ignored the largest, widest mass movement of our life times then it may have avoided the ignominy of the 2010 general election.

This, however, must be seen in context. Blairism and its commitment to market fundamentalism was a response to four general election defeats, the collapse of the labour movement, and the triumph of Western capitalism over the grotesqueries of Eastern Europe. It convinced many in the party and among its electorate that Blair's way was the right way (literally and figuratively) because it offered a story that helped make sense of what went before. Still, this isn't another essay on Blairism, but starting out with the proposition that class didn't matter it and the Milibandist sequel spent the next 21 years acting as if it didn't, with the election results to match. This story differs depending at the country you're looking at, but what is stark is centre left parties in Western Europe not only presided over similar policy menu, they did so while dishing out the thin gruel of austerity measures. In other words, they not only pursued a strategy that effectively meant they were organising against their base but ensured it would hurt them. Would you, for instance, want to vote for a 'left' party set on freezing your wages and ransacking your modest pension pot while threatening to throw you out of work. No, no one would, and indeed the left wing electorates of several liberal democracies have demonstrated just that.

The achievement of Corbynism then is, if you like, a reverse PASOKification. Labour in local government and Wales still administer Tory cuts, but the party now defines itself against them. Corbyn's politics, often derided as throwbacks to the 1970s, proved to be the most modern leftist politics because it spoke to the interests and hopes of millions excluded from the mainstream. Jeremy Corbyn and his immediate comrades understand that a Labour Party is supposed to stick up for working people and the poor, and if it does so it can build a coalition to win office and stay there. This is not rocket science, but is the most mysterious hocus pocus to anyone lacking the rudiments of a class analysis. Yet you don't have to be overly identified with the left to do this. Presently, Labor in Australia is polling consistently well and leading its Coalition opponents not because the party has a radical left programme, but because its agenda isn't about attacking its base: it's a straight forward anti-austerity position, a consistent Milibandism if you like. The New Zealand story is similar. Jacinda Adern's Labour is a far cry from Corbynism (despite getting hailed as its antipodean twin) and her government is quite centrist, but again, its holding on to its support (leading in the latest poll) because it hasn't (yet) gone down the road of attacking its own base.

Of course, the learned professor is entitled to disagree with this political explanation of Labour's rejuvenation, but the facts aren't with him. If First Past the Post isn't a dependent variable, how to explain Labour's collapse in Scotland without resorting to political analysis? What we saw there, as if we need to remind ourselves, is a thoroughly establishment party throw its lot in with the Tories and be seen to set its face against its own progressive support. No wonder the SNP cleaned up. The second problem is holding FPTP responsible for 2017's polarisation goes against the vote trends prior to that general election.

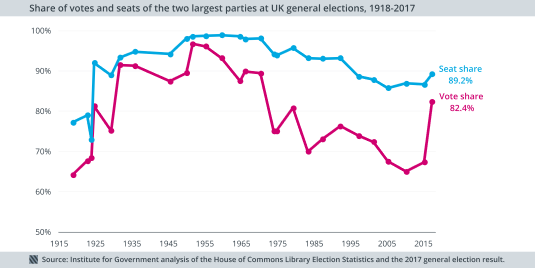

As the graph shows, and every student of political science should know (let alone decorated academics), the combined vote share for the two main parties peaked in 1951 and declined by about one third by 2015. The sharp reversal came, you guessed it, in 2017. If then the FPTP thesis is correct, then why did voters spend 60 years moving away from the two parties the electoral system doled out unfair advantages to? Could it be because of, gasp, politics? And would an analysis of the politics yield reasons for the return of polarisation?

Well yes, obviously. But not from the vantage of the ivory tower it seems. I mean, who could possibly think that Corbynism as a valid explanation of the reverse in Labour's fortunes is refuted by the larger vote share Theresa May's Tories managed to poll? They are not mutually exclusive but, rather, are mutually conditioning. The present Tory coalition of voters was more or less in place shortly after May made it to Number 10, and here she did two significant things. She sounded the one nation bell that, at the level of rhetoric at least, suggested the years of dog-eat-dog and beggar-thy-neighbour were coming to an end. In other words, as someone vaguely new to the mass of the voting public she had a distinctive and mildly optimistic stance vis a vis her predecessor. And she explicitly positioned the Tories as the party of max Brexit. That is you can trust the Tories to deliver it, whatever "it" may turn out to be. This helped cement a tranche of voters attracted by (cautious) change and a right wing, semi-authoritarian and anti-immigrant vision of Brexit. Who were these people? The petit bourgeois hungry for "leadership", capital - naturally, older workers in declining occupations and retirees. These are segments of the population particularly prone to Tory scaremongering and, thanks to the breaking down of the conservatising effects of age, are in long-term decline.

Jeremy Corbyn is a factor here because his person is a lightning rod for their discontent and fears. Everything he is charged with - hanging around with terrorist supporters, spying for the Czechoslovak secret police, campaigning against wars, expecting the wealthy to pay more tax - these pluck at the anxious heart strings of millions of people ill at ease with the world and for whom such matters typify their anxieties. Funnily enough, Theresa May and the Tories perform exactly the same role for the coalition Corbyn's Labour has built. In power, their policies mean continued misery, continued precarity, no prospect of accumulating property and getting on, crumbling services, and zero interest in the threat of climate change.

These are the contours and movements of British politics now, and our job is to analyse them, get a sense of the trends and direction and, crucially, use it to inform political strategy. In other words, a million miles away from the academic political science demonstrated above. It's less a case of faulty analysis and one of structural distance, of treating the behaviour of parties and the stakes they contest as objects of contemplation. From such a remove it can appear as if parties are free floating, that voters pay obsessive attention to the comings and goings at Westminster, and that electoral systems play an overdetermining as opposed to a subordinate role in political life. Some might say they are reified precisely to avoid having to get to grips with the complexities of politics as well as the awful, impermissible conclusion: that Jeremy Corbyn has, indeed, saved the Labour Party.

8 comments:

I agree. Your analysis is consistent and makes sense. I think what is more extraordinary is the resilience of the Tory vote despite over eight years of leadership ineptitude. Dave, it is is commonly agreed, is by far our worst post-war prime minister. May and her fractured team are almost cartoonish in their asinine blunderings. Yet, they remain on 40+% in the GE and in successive polls since then.

So, who are those people who continue to vote Tory? Well, I meet them every day. Like you say, they make up an interesting group: the property-owing, aged, petit bourgeois/small business, 'the old middle class' and a significant group of working class 'little Englanders', (the lot who assault you with poppies about this time of the year). When you speak with them, or venture into a discussion of contemporary affairs, their whole demeanour changes if you offer anything other than a narrow range of views (which is often described to me as 'basic common sense'). They spit out the word 'Corbyn', as if it's a disease. They pretend otherwise, but they are are eugenicists and live a life of petty prejudices. At the moment, their interests are being served by neoliberalism but there is an obvious tension between their wish for the border protection of 'economic nationalism' and the sweeping changes of a deregulated capitalism, which have ruptured their cherished national institutions. They are also fearful of robotics & surveillance, and of course, immigration. They are the people who 'punch down'. They go for the weaker, more vulnerable. This determines their values and humour, yet they want you to support any half-witted charity they are currently collecting for. A lot of them are the 'generation of 1968' who have lived through a long period of 'welfare capitalism' but are now narcissistically holding on to their triple-lock pensions, yet cheer-on every austerity measure. All told, a despicable bunch.

A question on economic nationalism: why has it focused more on keeping out immigrants rather than keeping out imported consumer goods?

Why hasn't the economic nationalist slogan of choice been something like "Hang the traitors who shipped our jobs to China!"?

The job's not done yet. The Blairites have been back on manoeuvres this last week or so. They're clearly up to something. I think they'll soon make their move.

“Why hasn't the economic nationalist slogan of choice been something like "Hang the traitors who shipped our jobs to China!"?”

Well as our in house dialectician has said, these people are a despicable bunch! We don’t want you filthy cunts here but please work your bollocks off so we can have cheap goods.

I have to say though that I fundamentally disagree with our in house dialectician when he says they “are also fearful of robotics & surveillance”. These people love surveillance, in fact I am amazed that our in house dialectician has never heard them say, if you have nothing to hide you have nothing to fear! They actually love robotics, see their faces light up when they switch their phones on.

I also have to find disagreement when our in house dialecticians claims these Tory voters are torn between their cherished institutions and economic nationalism, as if that is a recent phenomenon and not something they have managed to put up with for about 40 years!

Given household disposable income has steadily increased since 1977 I don’t see anything miraculous about the Tory vote staying steady at 40%, actually I am gobsmacked that in a nation like the UK Corbyn can be so popular. I never saw that one coming!

The Blairites are massing, like Sauron and his hordes, coming to destroy Corbyn and to continue to be the fake lefties and sell outs we know them to be.

There aren't enough of them to "mass", thankfully.

This is where being a top-down elitist project lets you down.

Hard to believe that a 'Professor' could make such an awful comparison between UK and German politics based on the voting system. You only have to look on Wikipedia to realise that German PR brought about a two-and-a-half party system for most of the post-war era, more so than Westminster elections in fact. Even as late as 2002 the two main German parties shared 77% of the list vote. As you point out, prior to 2017 the UK system had become much more fragmented in terms of vote share, reminiscent of recent Germany. In 2013 the CDU/CSU and SPD had 67% of the vote and Labour and the Tories shared 68% in 2015.

If you look at the recent fortunes of the PS in non-PR French elections then things look even more stark.

To suggest that Corbyn on the one hand and Brexit on the other haven't been responsible for a massive divergence in trends in UK and German politics is simply self-inflicted myopia.

Re: Australian Labor, a very interesting and useful piece from Osmond Chiu here

Post a Comment