As any socialist involved in labour movement politics will tell you, things haven't been too peachy these last 25 years. The awareness of socialist ideas are at an all-time low and total trade union membership continues to decline . A number of arguments have been put forward to explain this unfortunate political reality. For example, some locate the malaise in the strategic defeats our movement suffered at the hands of Thatcher's Tories in the 1980s. And others might suggest increasingly privatised and individuated lifestyles has left little purchase for a politics founded on collectivist principles. There are others too. One of which has had little impact outside of academia but can certainly give pause for thought.

Coming out of political science, the work of Ronald Inglehart has proven to be an influential argument in academic circles about the effects of a fundamental culture shift in advanced industrial societies. His position is this: there has been a marked decline in so-called materialist politics and a complimentary rise in 'post-materialism'. Or, to put it more crudely, the popular take up of bread and butter politics has given way to quality of life issues (which refer to lifestylist, environmentalist, and race/gender/LGBT issues). Inglehart bases his argument on two hypotheses.

1) Post-war capitalism in the West and Japan guaranteed a greater degree of economic security for a greater proportion of the population than had ever been the case. As Inglehart puts it “economic factors tend to play a decisive role under conditions of economic scarcity; but as scarcity diminishes, other factors shape society to an increasing degree” (1987, p.1289). These "other factors" are post-materialist issues and concerns.

2) In line with increasing levels of prosperity, Inglehart argued each generational birth cohort is born and socialised into a context where increasing numbers of people have only ever experienced economic security. Because of this newer generations will retain a certain predisposition to a post-materialist outlook throughout life (accepting the argument that early childhood experiences are the most psychologically important), and therefore as older cohorts die and are replaced by the birth of the new; and provided economic security remains, a respective spread and decline of post-materialist and materialist values is set in motion. Inglehart observes “differences between the formative socialisation of young Europeans and their elders were leading young birth cohorts to value relatively high levels of freedom and self-expression … [therefore] future intergenerational population replacement would bring about a shift toward new value properties” (Abramson and Inglehart 1995, p.1).

The relationship between cohorts and adherence to post-materialist values is not one of continuous and linear growth, but assumes a fluctuating upward tendency that is at times halted and temporarily reversed by economic slowdown and recession.

This is all very well, but what proof exists for this broad brush of an argument? Inglehart’s measurement of value change is based on surveys designed to gauge a respondent’s receptivity to material and/or post-material values. The sample is asked the set of questions and according to their answers are divided into 'materialists', 'mixed', and 'post-materialists'. Ignoring those of mixed views, he subtracts the number of materialists from post-materialists to yield a ‘percentage difference index’ (PDI) that can be measured and compared over time. For example the following data from his 1995 book, Value Change in Global Perspective, demonstrates an overall positive PDI trend, which, he argues reflects the growing saliency of post-materialist concerns.

PDI scores for Britain 1970-1 – 1993

Britain | 1970-1 | 1976 | 1980 | 1985 | 1990 | 1993 |

Post-materialist | 7 | 8 | 9 | 14 | 15 | 15 |

Mixed | 57 | 55 | 55 | 59 | 56 | 64 |

Materialist | 36 | 37 | 36 | 26 | 30 | 21 |

Total % | 100 | 100 | 100 | 99 | 101 | 100 |

Sample Size | 3,950 | 1,017 | 2,226 | 2,079 | 1,955 | 1,000 |

PDI Score | -28 | -29 | -26 | -12 | -15 | -6 |

This long-term development in Britain is shared by other advanced capitalist societies and has allowed Inglehart to make a number of assumptions about contemporary Western politics. He argues those who score highly on his percentage difference index (i.e. post-materialists) are more likely to participate in conventional mainstream politics, approve of "non-conventional" political activity (demonstrations, direct action, etc.), and tend to support left-wing parties in elections more frequently than their materialist counterparts. There is also the emergence of the "new" political family of Green parties and movements, who, in Inglehart's opinion, were unlikely to have emerged without the cultural changes that gave rise to a post-materialist world view.

If we accept the value of the argument it would nevertheless be a mistake to reduce the emergence of environmentalist parties and movements (along with others similarly concerned with quality of life issues) to just cultural shifts. Culture and cultural developments do not happen in a vacuum. They are tightly-bound to economic and political processes. There have to be other roots to post-materialism's saliency besides rising affluence. One school of thought contributes to understanding is as an outcome of the (old) social democratic state’s contradictory management of a capitalist economy. John F. Sitton summed it up thus:

The commodity form of value is what distinguishes the capitalist mode of production from other modes. If the system is to maintain its identity as capitalist, accumulation must continue through exchange relations, as opposed to forced labour or state command of production. The state must therefore find a way to “recommodify” capital and labour so that the paralysis is overcome without breaking the principle of exchange (Sitton 1996, p.112).

In the context of welfare capitalism Claus Offe has argued that state intervention assumes allocative and productive forms. The former refers to the ‘normal’ state functions of tax utilisation and the use of resources already under its control. The productive functions, on the other hand, are where the state attempts to recommodify labour and capital. Here the state, as a capitalist state, is compelled to intervene when the costs and risks associated with capitalist competition cannot increase productivity further. It therefore attempts to ‘jumpstart’ the system by baring the cost of providing new inputs, stimulating markets, regulating labour, and opening new avenues of capital accumulation which strengthens trends towards the universalisation of the commodity form, which is a property the Keynesian state shares with its neoliberal successor.

This kind of interventionism is problematic for the formation of class identity and consciousness. For Offe this has led to a number of developments: individual achievement, prosperity, and even social deprivation appear to be de-coupled from class position. The interest group orientation of state intervention is mirrored in the fragmentary character of electoral politics. And the development of white-collar ‘service employment’ has generated a significant dislocation in the unified experience of the working class. These processes condense to displace the salience of identity centred on the workplace, undermining the appeal and scope of collective class politics.

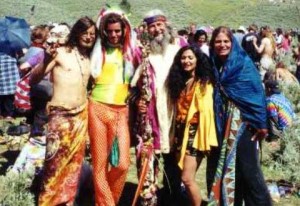

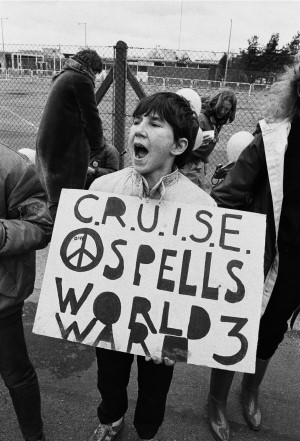

These same processes have meant a multiplication of the points of social conflict in Western societies (though not necessarily their intensity). Whereas Marx argued the trajectory and fate of capitalism would be decided by the contest between bourgeois and proletarian, recent developments of contradictory processes appear to call more diffuse political actors into existence who are opposed to aspects of the system rather than capitalism in its totality. For Offe new social movements arise from these apparently "non-class" cleavages and adopt identities that appear independent of class position. The peace movement is cited as an example, noting how it would not exist without the state’s “Keynesian” consumption of armaments. Secondly, though many NSMs are not consciously anti-capitalist, the implementation of their political demands may sit uneasily with capitalism, and could therefore generate more areas of tension in the future.

In sum the class compromises that made possible the post-war boom ultimately corroded the political economic base of the social democratic state by providing secure conditions for post-material value and culture change, and facilitating struggles that eschew a class identity. Therefore it is possible that if Keynesian welfarism had persisted, the decline in the efficacy of class and labour movement organisations would have continued. But in Britain’s case, it is arguable this process accelerated under the impact of largely successful elite attempts to move away from the politics of compromise in favour of a new settlement primarily beneficial to big business.

If we accept these arguments, it does not mean socialists should go the whole hog and abandon class. As Inglehart acknowledges 'materialist' (i.e. class) issues can become more salient when capitalism is confronted by crisis, but also it demands we have to be a bit more imaginative when it comes to political strategy.