Drawing on recent pieces from boring American writers, John Lloyd writes about how neoliberals of the left and right have attacked trade unions and undermined them by unpicking the post-1945 consensus. Quite, which is a reason why Blair was a bad 'un, even if you box out the calamity of Iraq and price in all those PFIs. This undermining of union power has left workers unable to organise effectively, which has seen the productivity gains of the last 40 years accumulate in the hands of the wealthy as living standards have stagnated and, as I'm writing, are going backwards. And, to dust off the frightful phrase, there is the social capital argument. The experience of active trade unionism forces workers together into collaborative relationships, and writ large across a given employer, multiplies social contacts. The workforce become more cohesive, less atomised, and the broad consequence is the building of social trust. Cynicism does not have to be the default.

Not much to disagree with here, but to make it past the Tory filters there must be a sting in the argument, yes? Sort of. Despite highlighting the point unions are "lobby organisations for the overprotected public sector" and how UK unions have come to rely on state-provided services for its industrial backbone, there's a whistful paen to non-political trade unionism. Oddly, new small militant unions like the Independent Workers Union of Great Britain and the United Voices of the World are talked of in positive terms because, at least as far as Lloyd is concerned, their militancy is grounded in the day-to-day challenge of organising precarious workers and ensuring they get their fair share. If the patchwork of society could be sewn together in like manner, especially among "lower class politics" (his phrase) then extremism can be seen off and atomism overcome. Happy times are here again.

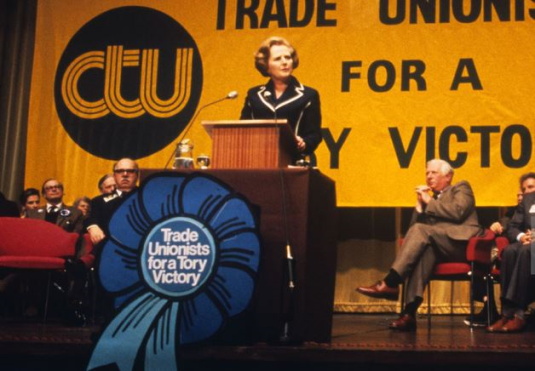

Why is this a conservative case for trade unionism? Because it argues for an ideal-typical trade unionism that is a throwback from where we actually are. In the first place, there is nothing new about these points. Conservative Trade Unionists were a body of some not insignificant clout in the workers' movement during the 1970s and, at its height, organised tens of thousands of Tory trade unionists. None of this should come as a shock. To use a phrase from one of the old beards, trade unionism is the bourgeois politics of the working class. Pay, discipline, safety, hours, bullying, these are the everyday issues faced by union activists, stewards, officers, and branches. In a period of labour movement ascendency, like the 1970s, collective action and the strength of workplace organisation delivered results. Struggle helped worklife get better and made sure it paid more. Depending on the politics of a particular workplace, this could intersect with socialist politics and lead to Labourist or, indeed, revolutionary conclusions. But equally, in the absence of politics collective struggle becomes a means of reconciling trade union activity to the system. The rounds of collective bargaining backed by thr strike threat, or even wildcat strikes over sackings of convenors and stewards, or new working practices at their most militant might have challenged management's right to manage, but did not, by and large, raise wider questions. Even if, as was often the case, stewards and key activists were Trotskyists or from the Communist Party. Trade unionism in the post-war period might have made socialists out of hundreds of thousands, but its success ensured millions more were not politicised. This system of institutionalised class struggle worked for them.

This non-political trade unionism tended toward Labourism: trade union stuff is up to the workers, but leave the wider politics of labour to the professionals. But Tory trade unionism had the same root: the union was a place of knowing one's station in life, of guaranteeing community at work while promoting contentment with how things were. Too much militancy was disruptive and threatened workers' security and livelihoods, and this from the standpoint of the CTU was their mission: to preserve and, unsurprisingly, conserve. When Thatcher began her assaults on the labour movement, the bulk of the CTU were unperturbed: the workers' movement had become "unreasonable" and "irresponsible" and needed the state to bring it into line. The layer of conservative trade unionists and working class Tory supporters generally saw it as harsh but necessary medicine, and some were happy seeing the "disruptive" miners getting a good hiding. This famously included one Patrick McLoughlin, a working miner (then a Tory councillor, later a grandee) who denounced the strike from the floor at 1984 Tory conference. If trade unionism had steered away from politics and kept the extremists from power in the movement, none of this might have happened.

Some far-sighted right wing thinkers are alive to the importance of class struggle to their system, and not just in terms of workers having enough wages to avoid crises of underconsumption, as per the present. An active, trade unionised work force is a pain in the arse for management, but it forces them to innovate to intensify exploitation and replace workers with machines, thereby retaining control over work and boosting productivity. It's a creative tension perspective, and without it productivity stalls, low paid jobs proliferate, and we end up with something looking not unlike the British economy of the last decade. The Tory fantasy of quiescent, non-political trade unionism in the 21st century is a fever dream of a cap-doffing working class who'll happily work with them to grease the wheels and, ultimately, do themselves out of their jobs. As was the ultimate fate of so many CTU supporters in the 1980s and 90s.

A multitudinous mass of good workers who'll do their duty, shop til they drop, and inculcate a new class culture of deference, communitarianism, and perhaps a bit of "suspicion toward outsiders". Lloyd says this conception of trade unionism is "humanist", not political. He could not be more wrong. Sectional to its core the whole argument is sodden with bourgeois assumptions and the sense of a misty-eyed reactionary pining for a better yesterday. A conservative case for trade unions certainly, and one a million miles away from ours.

2 comments:

«their militancy is grounded in the day-to-day challenge of organising precarious workers and ensuring they get their fair share. If the patchwork of society could be sewn together in like manner, especially among "lower class politics" (his phrase) then extremism can be seen off and atomism overcome. Happy times are here again.»

That's the "tory" case for trade unionism: unions as guilds, within the context of "one nation" paternalism, that of incumbents in privileged social status.

But the Conservative party policies for the past 40 years have been mostly "whig", where social relationships are not paternalistic, and even "tory" trade unions are seen as obstacles to the power of those who are powerful in the markets, those who are incumbent in privileged market positions.

The difference between "tory" right and "whig" right became only obvious in the french revolution of the late 18th century, so it is still easy to forget, but it does matter for things like Conservative attitudes to trade unions, as the Conservatives are a coalition, as our blogger keeps reminding us.

«the importance of class struggle to their system, and not just in terms of workers having enough wages to avoid crises of underconsumption, as per the present. An active, trade unionised work force is a pain in the arse for management, but it forces them to innovate to intensify exploitation and replace workers with machines, thereby retaining control over work and boosting productivity.»

That something that can only matter to the "tory" right, to a limited extent; for the "whig" right, the market does all that. And in any case both "tory" and "whig" right would rather their rents and profits were lower than to lose control to overly active workers, would rather have a permanent semi-recession (as in most of the period since 1980) than workers be in a position to be "uppity".

«This system of institutionalised class struggle worked for them.

This non-political trade unionism tended toward Labourism: trade union stuff is up to the workers, but leave the wider politics of labour to the professionals. But Tory trade unionism had the same root:»

There is a simple question: when is capitalism going to end?

#1 If it is "within several years", why compromise, the vanguards of the proletariat should go for the political power of the trade unions now, and "one last heave", one last "general strike" will deliver the soviet paradise.

#2 But if the answer is "not this century and perhaps not even the next", then perhaps the politics of driving a harder bargain while keeping alive the longer term aims would be more realistic than planning the transition to socialism while singing the "Red Flag".

Thanks in part to #1 attitudes in 1983 voters chose “a fundamental and irreversible shift in the balance of wealth and power in favour of [property and business rentiers] and their families”.

Which is what we still have now, and what "worked for them" is better than that. V Ulianovich when asking "What to do?" warned wisely against both opportunism and adventurism. Conservative trade unionism is and was opportunistic corporatism, but then syndicalist trade unionism in retrospect was foolish adventurism.

That swedish social-democrat said social-democracy was the art of most plucking the capitalist goose with the minimum of hissing.

That gives for granted that the capitalist goose has to continue to exist, thus disappointing those who wanted to ascend from the NMU to be the new ruling class as "Supreme Commissars of the People", but the swedish formula for quite a few decades "worked for them".

Organizing workers for a better deal within the current system is not mere opportunism if the longer term aims and work for a better system are maintained. It is not easy: it is easier to just give up on the longer term aims and become corporatist (see SDP), and it is easier to forget the reality of the existing system and dream of the future soviet paradise (see NMU).

Post a Comment