The new wave of technology, the so-called Fourth Industrial Revolution, does pose a number of significant problems to business and anyone concerned with defending its class basis. There are issues posed by intangible commodities, the political problem of tech-enforced mass unemployment, the ongoing shift to immaterial labour (which the emergence of these technologies is accelerating), and the increasing visibility of exploitation it fosters. We should bear all this in mind as we approach Alan Mak's new Conservative Home pamphlet on the Fourth Industrial Revolution.

As a technocratic exercise, there are moments where Alan's thoughts aren't entirely merit-less. For instance, Local Enterprise Partnerships would, under Alan's plan, have the responsibility for putting together 4IR strategies for their area. Not a bad suggestion in principle, but not all LEPs have the expertise necessary to undertake the necessary mapping exercise this would require, nor the resources either. The businesses who sit on the LEPs are unlikely to cough up the cash, so it would fall to squeezed local authorities - unless the government releases funds in support. The second issue is councils often sit in more than one LEP, which could mean a recipe for mixed up strategies and (political) problems arising from recommending something with favourable economic multipliers in one district but not another. His second proposal is a National Institute for Artificial Intelligence and Robotics, a hub bringing together academia and industry. Again, there's nothing inherently objectionable about this provided it's resourced properly. He also recommends a national skills audit to aid strategic investment and what he calls lifelong learning accounts, an idea not a million miles away from Labour's own lifelong education service.

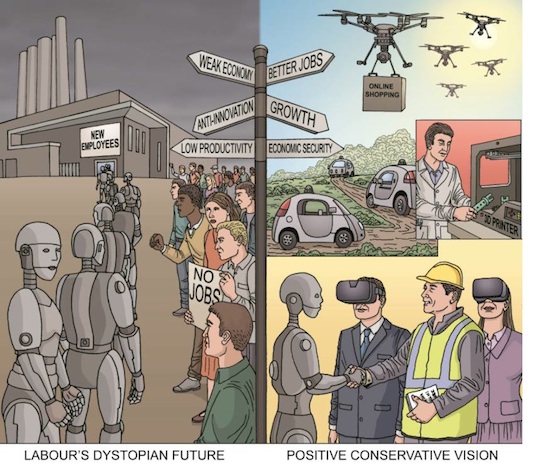

And that, I'm afraid, is it. The plusses of a 40-page pamphlet easily summarised in a single, short paragraph. The rest? Oh dear, the rest. Where can we begin? Well, there are the obvious idiocies. Take the pamphlet cover (above), for instance. Apparently, the future Labour favours is one of robots in the factories and workers on the dole. And yet, in spite of himself, Alan argues throughout that this grim vision is one Labour is shying away from. He attacks Jeremy Corbyn and John McDonnell for their robot tax and says they're proposing "heavy regulation" that would do "untold damage" to the economy. If this is the case, how can we arrive at a point in time where robots are pushing workers out given this would require a great deal of innovation and zero regulation? You can't have it both ways, Alan. Labour either wants to replace workers with robots or not. Also, according to the cover, the Conservative future is a world of driverless cars ferrying nobody to and fro, and a bargain between workers and robots while management are wowed by VR. I know a lot of bosses like spending time in their own realities, but I'm not sure this is what our Tory friends are trying to convey.

Alan's criticisms also misfire. Throughout, we're told Labour is hostile to innovation and would hold Britain back. Yet we find on page 20 Alan urging his government to spend the equivalent of three per cent of GDP on R&D, as per, um, Labour's 2017 manifesto commitment. Such "forgetfulness" is extended to a few weak jibes at the European Union. On the same page, we find him railing against "the precautionary principle". i.e. Article 191 of the Lisbon Treaty. Alas, Alan isn't being entirely honest here. The Article governs the formulation of EU environmental policy. Burrowing further, in the principle's explainer, it may be invoked if there is a possibility a new process or product might be dangerous. For Alan, this "unreasonably burdens" innovation. Do we really have to go over the history of adopting new technologies to establish that the precautionary principle is informed by centuries of experience? Bizarrely, and somewhat incoherently, he sort of agrees. When Britain leaves we should adopt a "British Innovation Principle" alongside the existent rules to make the UK a broiling laboratory of new thoughts and invention. That's all very well, Alan, but you can't innovate without the readies and the EU, the Tory right byword for bureaucracy and inefficiency, finds it spending an average of 2.0% on R&D versus the UK's 1.7%. And Germany, the heart of the leviathan, invests some 2.9%. There is nothing about EU membership holding Britain back. It's the Tories, their utter uselessness, and the decadent class they represent.

The content of this "innovation principle" is, as you might expect, a total dog's dinner. As Alan puts it (p.21):

The British Innovation Principle would place a statutory duty on all public-sector bodies to ensure that, whenever policy or regulatory decisions are under consideration, the impact on innovation as a driver for jobs and growth is assessed alongside any potential risks from technological development.Let me get this straight. The Precautionary Principle is overly risk averse, but Alan wants to keep it. Meanwhile, Alan wants to add costs to the public sector by enforcing innovation audits. Colour me sceptical. In practice this will require a ridiculous amount of socially useless work quantifying "innovation", the introduction of innovation targets, and its unworkable fetishisation. Anyone familiar with higher education knows the pressure coming from government and institutions about "innovative teaching", whatever that means, and how inessential gimmicks are key criteria of the Teaching Excellence Framework. The result in all cases is a slow down in operations which, yes, depresses spontaneous and serendipitous innovation because everyone's too busy chasing targets and filling out pointless forms.

Must we go on? I'm afraid so. Addressing himself to the forecasts of a jobs apocalypse, Alan notes we shouldn't see a trade off between innovation and jobs. They are partners. And to demonstrate this, he cites the example of the Siemans factory in Amberg. Application of new technologies has seen 75% of production automated and a 1,000% increase in productivity. "But", Alan breathlessly intones, "the workforce has remained the same size!". Ah, I love me some stupid empiricism. No, what it means is the old model that linked productivity expansion to job creation has massively imploded. In the future, Siemans workforce will remain static and do nothing to increase the availability of work. The jobs cut are those that would have otherwise been required down the road.

And the rest of the pamphlet? It's just piss and wind. Mindless boosterism accompanied by witless attacks on Labour, and little else. Believe it or not, this is the best the Tories have on offer. Consider Labour's high technology vision, central to which is a world where new technology is harnessed to free people. For Alan, 4IR's exciting potential lies in fridges being able to order milk while you're at work (which then goes off because you still need humans to put them in the fridge). The Labour vision involves freeing people up from work to give them time to do other, more enriching and socially productive things. Small wonder Alan finds this a dystopian idea. Labour's policy is aimed at realising the radical potentials of the new wave of technology, while the Tories want to curb this and adapt the new to make more money for their interests. What a dismal, plodding view of the future, a world where littlehas changed and the benefits of robots, new information technologies and additive manufacturing accrue to the same old same old at the top.

3 comments:

As Chris Spence points out on Twitter, it appears the bloke in the image above has his VR goggles on upside down.

And the wrong way round.

He represents management.

Post a Comment