We live in a society that makes a fetish out of work. One's trajectory through the education system is (supposedly) guided by getting a decent job at the end of it. People's engagement with social security is supposed to be a temporary thing with the object of throwing them back into the workplace at the earliest opportunity. And if people aren't working, they're feckless and bone idle and made to feel that way - never mind how unemployment always exceeds the number of vacancies. And you know what? It's all so bloody unnecessary. While there are people without jobs, plenty of those with them are overworked. Work time too often bleeds into home time as work loads are impossible to manage as task piles upon task. Or at any time the phone threatens to go with a "request" to come in, shattering your free time and reminding you your time is their largesse. Too many workplaces are permanently short staffed, and the experience of work is a dizzying affair of plate spinning and routine. Life isn't for enjoyment, it's a treadmill for countless millions who realise when they reach retirement that they're too knackered or too ill to do the things they always wished to. Life is far too short to be spent and bent in involuntary servitude, especially when work can be planned and shared out equitably.

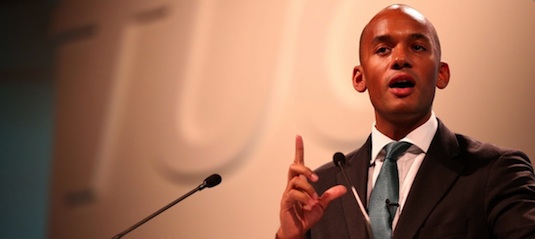

I wasn't surprised to find Chuka's much trailed opposition to the basic income couched as a defence of the cult of work. Nor that his argument is virtually identical to criticisms previously ventured by Yvette Cooper. That doesn't mean it isn't irritating, or won't be taken seriously in some quarters. But seriously, just look at the state of it. Nonsense about basic income meaning people living off the state, living vacuous, purposeless lives, of "giving up" on creating new jobs, it's a miserable exercise in how impoverished the political imagination can become. For instance, in the coming wave of automation,

Work could become more fulfilling. In the new economy our most valuable asset will be human beings. We have emotional intelligence and perception, and the capacity to create, empathise, persuade and reason in abstract ways. We can make imaginative leaps, and we have intuition. In the new economy what will have added value is what is devalued today – the emotional labour of caring, communicating, creating and connecting.

As if all this is dependent on the archaic compulsion of exchanging our capacity to labour for wages or a salary. Technology should not be deployed to create more bullshit jobs so more people can spend their best years doing meaningless, socially useless tasks. It should be deployed to reduce the working week, to spread the wealth we create, and to make us free from the necessity of waged labour. The future has to be something better than a human being chained to a desk, forever. And it totally can be.

What the basic income offers is a guaranteed, no-strings income to all. If money means freedom and choice, this is exactly what it confers. It allows people the choice to spend their time engaged in socially productive voluntary work or to sit at home and play video games. People have the freedom to indulge their passions. They can engage in entrepreneurial activity without the risk of ruin, as individuals, small partnerships or cooperative ventures. They are free to dip in and out of the education system, and do so without having studying time eaten up by work. And likewise, people can retire early from work, raise a family, attend to full-time caring without worry and insecurity. We know a basic income can do this, because trials prove it.

Yes, there are basic incomes and basic incomes. It has its fans on the right as well as the left. For the former, informed as it is by Californian tech-bro libertarianism, establishing a basic income allows for the abolition of social security and a whole bunch of liabilities companies shell out for. The basic income is a way of socialising risk, and helping support a population while Silicon Valley capital parasites off its data. Others favour pitching the basic income at a very low level so it doesn't intrude on work incentives. i.e. The necessity of working. Left approaches to basic income should reject both and pitch it at a level that allows for a comfortable life that reproduces human beings in all their material, social and cultural complexity.

Would this present a capitalist economy severe difficulties of adaptation? Absolutely, but then we're supposed to be in the business of moving beyond markets and artificial scarcity. If capital wants to survive, it would have to transform the nature of work entirely. Without compulsion, suddenly the (potential) worker has the upper hand in the capital/labour relationship. Capital would have no choice but to innovate and automate as much as it possibly can, because to attract employees, wages, which would truly become compensation for people's time, would have to be much higher than they are presently. The conditions of work would have to be better. Work would have to become more rewarding and enriching. And, who knows, because work would be done by people who want to be there perhaps it might be a more pleasant experience all round. Meanwhile the rest of society would move away from the commercial imperative, experiment with new ways of organising things, and as everyone has a guaranteed good standard of living may decide to consign money itself to the museums.

It's this, ultimately, which underpins the hostility Chuka and his friends have toward the basic income. Theirs is not a pragmatic acceptance of studies that prove work is good for you but a deep seated fear that the principle of a basic income, once established and practiced, is something that works against the very logics of compulsion and class struggle capitalism is dependent on. And that is reason enough to support it.

14 comments:

The final paragraph presents, in a nutshell, the basic issue beyond

Basic Income. We are living in the time when capitalism is confronted with its own mortality. Its productive capacity has been reached, and the outline of a foundation for its successor is being unfolded. Interesting times indeed.

I'd seen that a number of councils in Scotland were considering introducing a Basic Income. I have considered the possibility of moving there to obtain this free money. For me and my wife both having retired, and being paid pensions the idea of somebody giving us both several thousand pounds a year more for nothing is appealing.

However, it does sort of show the problem with the idea of such a basic income. We would be receiving this value without adding any additional value into the economy of the council area that was paying it to us. Neither of us have any intention of going back into work, now that we are in receipt of pension, and we would have even less incentive to do so if someone was prepared to pay us both several thousand pounds more per year.

What we would be doing, of course, is spending some of this value given to us, for which we had given nothing in return. If several thousand more people in a similar situation followed our logic, and moved to Fife, for example, the immediate effect would be a large rise in monetary demand for houses in that area, pushing up local house prices. And, of course, we would be placing additional demands on local hospitals, social services and so on. Whilst we might be paying for some of those things in Council Tax, that would only be giving the Council back a portion of the money it had paid us in UBI, without us giving anything in return for it.

If the Council was not to go bust as a result of paying out these amounts for UBI,and its increased costs for service provision as people moved into the area to obtain the free money, it would have to negate the effect of the UBI, by raising its charges for services, and increasing the Council Tax to cover these increased costs.

Th effect then would not just be an inflation of local house prices, but also an inflation of the prices of local services etc. The money illusion of the UBI would then evaporate in a puff of inflationary smoke.

I think you're behind the curve on basic income - put simply, it abrogates the duty of the state to create opportunity and remove the obstacles to the individual to fulfil their potential (Isiah Berlin wrote on negative/ positive freedom). Paradoxically, it is more of a tool for a neo-liberal than a socialist. Furthermore, it is based on a flawed understanding of real economics and is unlikely to see low wages rise, on the contrary, it is likely to see an increase in indigenous joblessness, so you'll basically further the divide between migrants, who'll be doing the work, and "natives". You're also wrong about the link between income and satisfaction, most surveys measuring happiness tie this to a sense of value through work, not income.

"your experience of work is a life of drudge, humiliation and insecurity"

What a dreary, narrow view of life you Marxists have!! The great majority of people I meet, both "working class" and "middle class," actually enjoy their work. That doesn't mean they don't want holidays or weekends, but it does mean they wouldn't want to be unemployed, even the dole paid as much as their previous wages. This applies especially to the self-employed.

I find your view of work to be extremely defeatist. The answer to work being "drudgery, humiliation and insecurity" is to change conditions in the workplace, which is best achieved through collective action by the workers themselves.

I've often heard work involving personal care of sick/infirm people described as "menial" "humiliating" and other negative language. I did that kind of work for years and the only thing I disliked about it was the way I was treated by slightly more senior colleagues. Wiping bums and washing bedpans is not intrinsically humiliating- it's the low status ascribed to people doing that sort of job, and the way other people feel free to treat them based on that low status. The answer is to raise the status of important jobs and get away from the idea that a job where you have to wash at the edn of that day is inferior to one where you don't.

It's also defeatist to assume we can't resist automation. We should celebrate the Luddites! The jobs that are most threatened by robots are NOT the basic personal care jobs, but routine office jobs in the immediate future, and professional jobs (doctors, lawyers, teachers) in the not-so-far ahead.

Boffy's Fife manoeuvre would only be possible if the basic income were additional to the state pension, but in reality it would be a replacement. To put it another way, a basic income can be thought of as an extension of the state pension to all adults (incidentally, a UBI might well lead to an increase in the state pension, but one that was offset by an increase in the taxation of private pensions and capital).

In practice, the implementation of a UBI would probably have no immediate impact on most workers. If you earn enough, the UBI is simply offset by increased tax, while if you earn little, it will simply replace tax credits. A UBI is not a magic pot of new money, it is a progressive reform of the tax system (whihc should also mark a shift to greater tax on capital & land) that removes conditionality from the provision of basic needs, so reducing the coercive power of both the state (contra Umunna) and capital.

The prize of the UBI is not what happens on day one but what happens in the future, which means you have to think about it more in terms of its structure than simple cash. A socialist basic income should have two key characteristics, which would clearly differentiate it from right-wing and libertarian versions that seek to shrink the state or dissolve social responsibility through an appeal to a spurious self-reliance.

First, it would not substitute for the welfare state (the NHS, social housing, contingent benefits etc) but would be complementary. This is because welfare is concerned with the reproduction of labour while a UBI is concerned with the flourishing of the individual. They are related, but they are not the same. This is why arguments that claim that all work is detestable are irrelevant, but also why we should continue to pool lifetime risk socially.

Second, the purchasing value of a UBI would not only be well above the level of subsistence, it would be regularly updated as a social dividend. This means that growth (which currently disproportionately goes to capital rather than labour - i.e. profit rather than wages) would be more equitably shared with all members of society. While this simply means that the struggle for resources in an economy shifts, it does so in a way that is democratic, thereby mitigating the secular decline in the power of organised labour (as an aside, this is one reason why some labourists are sceptical, hence Chuka Umunna can find common cause with John Cruddas).

On Speedy's point about competition between native and immigrant labour, if the UBI is an entitlement of citizenship, then it will actually serve to depress immigrant labour supply at the lower-end of the wage scale. This is because wages can then fall to a lower marginal value (the UBI obviates the need for a minimum wage). In simple terms, if a job is paid at £8 an hour today, a future UBI of £5 (i.e. £175 a week) would mean the wage could reduce to £3.

A reduction of £5 an hour would be small for high-pay jobs, so the supply of foreign doctors and bankers won't dry up, but such as reduction would be massive for low-paid roles. The consequence would either be an increase in lower wage rates (which would initially benefit natives more as they would now have a lower marginal preference - i.e. the point at which it is worth working) or an increase in automation and thus productivity (which would feed through to GDP and so the UBI).

I'm outlining the above not simply because I'm an advocate of UBI but because I think discussion of a UBI is a way of approaching more fundamental issues such as the balance of power between capital and labour, the distribution of the fruits of growth, and society's responsiblity for individual dignity.

The fundamental problem with Umunna's contribution is that he is simply recycling arguments from the 1970s: that the state should retreat and the market should provide (of course, these now-hoary neoliberal nostrums can ultimately be traced back a further century). I don't get the sense that he has thought deeply on the subject at all.

David,

I think your interpretation of the UBI is wrong, certainly in terms of the explanations of it that I have ever seen. The idea of a UBI is that it does what it says on the tin. It gives everyone an equal minimum sum of money, whether they are currently in a £250,000 a year job, a Minimum Wage job, or on the dole, or receiving a pension.

It is a starting point not a replacement for any other income or benefits. So, for someone like me receiving a works pension, it would be an additional sum on top of it. Otherwise, it would represent a massive marginal rate of tax for anyone who started to get a pension or some other form of benefit, or who went into low paid employment.

For example, suppose the UBI was set at £7,000 a year, and someone found a Minimum Wage job of £15,000 a year (let alone if it was a Minimum Wage job for only 20 hours a week, so that their weekly wage was only £7,500 a week. If getting this job then meant they were earning above the UBI, and so lost the UBI, it would mean that from that alone they would face a 50% marginal rate of tax, even before actual Income Tax and NI were deducted. If they only worked for 20 hours, and earned £7,500 a week, the loss of the UBI of £7,000 would mean they would work 20 hours a week for just £10, or £0.50 an hour, which would mean no one in their right mind would take up such employment.

Good review here, pointing out benefits and drawbacks.

https://www.tuc.org.uk/research-analysis/reports/universal-basic-income-and-future-work

Steve

In this context, have you (or anyone else) read Precariat by Guy Standing? I don't agree with all his analysis but he elucidates the difference between labour (thing done in exchange for money) and meaningful work, much of which is voluntary or unpaid. So I really recommend that for an elaboration of what you're describing here.

https://www.theguardian.com/profile/guy-standing

I gather he has written another book recently which I can see I'll have to read as he's had some fascinating thoughts.

BTW, on the topic of automation, Hawkwind offered their thoughts on the matter.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bsQw-J4zAec

I would add to Anonymous's comment re wiping bums and yours re automation. No, I'm not talking about a bum wiping machine, but again, you are barking up the wrong tree re unemployment - since the Industrial Revolution the coming of new technology may have spelt the end of one profession (Luddites) but it has meant the beginning of a new. New technology is constantly creating new and unimagined opportunities, and always has done. It might also bump up the value of bum wiping: as manual labour declines the value of jobs which require empathy may increase.

Boffy,

The only agreed definition of a UBI is that it should be universal (all citizens get it), basic (sufficiently above subsisdence level to allow autonomy) and monetary (i.e. not benefits in kind). Beyond that it is up for debate.

A UBI would be additional to a private pension, but I suggest that it wouldn't be additional to a state pension. Given that a reasonable UBI would be roughly double the value of the current state pension, this would be a net increase for many.

Someone who got a minimum wage job would not lose the UBI, and only their income above the UBI level would be subject to tax. In the scenario you describe, a person on a UBI of £7,000 p.a. who got a job paying £15,000 would only be taxed on £8k (15-7).

What the rate of tax would be is a separate matter. My personal preference would be for greater gradation and for rates to apply to total income. For example, we could start at 1% and increment at that rate for every £2,000 of taxable income up to 60% at £120,000 p.a. (i.e. a total income of £127,000, including the UBI). In your scenario, this would mean paying 4% tax on £8,000, i.e. £320. Someone earning £150k a year (including UBI) would pay 60% on £143k, i.e. £85,800 in tax, leaving a net income of £64,200 (£57,200 + the UBI of £7,000).

Speedy,

It's always worth remembering that the Luddites were not (contrary to myth) protesting at technological unemployment but the use of technology (powered looms) to force down wages by expanding the labour pool to include less skilled workers (notably women and youths).

New technology does not appear because people have random lightbulb moments but because capital sees an opportunity to exploit labour at a higher rate, either through increased productivity or by deskilling. The labour market reflects the relative strength of these two tendencies. At the moment, we're biaisng towards deskilling, hence flatlining productivity, a growth in low-paid work, and even the substitution of labour for capital (the car-wash paradox).

Bill Mitchell had an excellent blog post on this area...it's nothing new. We've had this issue from the first industrial revolution, hence Luddites and Saboteurs. A combination of targeted government funding of public work and employment for public purposes is a far better price and automatic fiscal stabiliser than mass unemployment.

Please have a good read.

http://bilbo.economicoutlook.net/blog/?p=37361

That hardly seems fair, does it? Why should someone who puts a part of their wages into a private pension be able to receive it as an income on top of the UBI, whilst another person who puts the same portion of their wages, via NI and Income, VAT etc. into the provision of a state pension not get it back as a pension on top of the UBI.

In any case, that is not my understanding of how it would work, because it is supposed to be what it says on the can, a Basic Income that everyone receives irrespective of any other income, pension etc. The basic state pension is around £7,500, so that would mean that if you reckon the UBI would be double that, it would have to be around £15,000 per person. That is way in excess of the figures I have ever seen, and seems hardly sustainable.

No. The only serious analysis of the nature of human Labour is Marx's. He understood that capitalism alienated man from the Labour process

Here's part two of Bill's blog, part of a series leading to a book on the future of work.

http://bilbo.economicoutlook.net/blog/?p=37429#more-37429

Umemployment is miserable and doesn't lead to an upsurge in creativity. It also effects security and fear of the rest of us.

Post a Comment