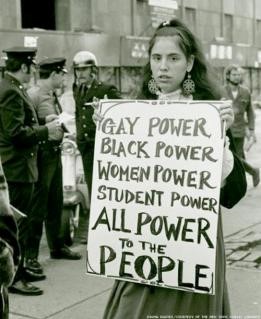

1. Intersectional thinking, informed in general by some kind of identity politics/new social movement theory accepts, in the abstract, that gender, race/ethnicity, sexuality, etc. are constituted by and through social relations. These relations are also relationships characterised at greater and lesser degrees by domination, discrimination, subordination, oppression, inequality, and silencing.

2. While acknowledging it in theory, the relational character of oppression tends to recognition in the breach than in the observance. Intersectionality is too often identified with the breakdown of attempts to think through the ways multiple oppressions work together, when its promise lies in overcoming their compartmentalisation. Intersectionality is not about an inverted hierarchy of oppression, scoring points for having it worse than others, or privilege checking as a precondition of solidarity.

3. The compartmentalisation of oppressed social locations is neither a matter of faulty theory or misinterpretation, but an effect of how the social relations constituting these positions work. It is an outcome, condensed theoretically, of experience. One cannot help but notice, for example, that the UK's new, post-Twitter generation of prominent feminist voices tend to be white, alumnus of top universities, reside in London and have solidly middle class backgrounds. The problem of which "we" these feminists speak of and for finds itself replayed 30 years after bell hooks diagnosed the problem in the seminal Ain't I A Woman?. But it's more than a question of who gets more CIF slots and retweets. It's a symptom of an underlying political economy of oppression, of being disadvantaged in some circumstances and benefiting from advantage in others. It is the latter that tends to generate axes of tension, making axes of solidarity based on shared characteristics difficult.

4. There are theoretically possible routes out of the impasse. The first of these is intersubjectivity. Sloppy, pathologised forms of identity politics valorises the unique qualities of one's subject position. No straight white man can hope to understand what it's like being a gay black guy. An impassable gulf separates able-bodied from disabled feminists. This, of course, is utter nonsense that fetishises oppression instead of challenging it. We are thinking, feeling, empathising creatures. Human beings are not cold appendages of interests, arrived at schematically. Social divisions do not prevent the more privileged and advantageous from sympathising, solidarising and allying with the oppressed - the history of each and every radical social movement tells us that. Likewise the reverse is true - our capacity for empathy is tugged on to shore up support for the arrangements ruling over us. The millions who grieved for Princess Diana. The millions who identify with celebrities. On and on it goes.

5. Intersubjectivity is a necessary condition for overcoming the pathologisation of identity politics, but is not sufficient. Taken in isolation it has its own dangers. In short, it can amount to an over-theorised notion of simply being nice and respectful or, as Bill and Ted might put it, being excellent to each other. In so doing it reduces sexism, racism etc. to matters of ignorance or individual nastiness. Questions of power are not relevant, they are pushed out of the picture.

6. The other is to give up on coordinated intersectional politics entirely. Just stick to ploughing your own identity furrow and let others get on with theirs. Laissez faire will sort things out, one hopes. Or dust off a master category and subsume everything to that by treating other differences as secondary. In both cases, this is a recipe for less efficacy and more pathology.

7. Perhaps understandably, intersectional thinking has tended to overlook class. Like gender, like ethnicity, like sexuality, like disability, class is a dynamic social relationship systematically reproduced across capitalist societies that is absolutely essential to its reproduction.

8. Too much received sociological commentary reduces class to status or, worse, occupational category. While important and vital to social critique and intersectional politics, an understanding of class as a relation, as a process takes us into capitalism's guts. And what we find there is a simple, banal truth that intersectional politics has forgotten. The overwhelming majority of people have to work for a living.

9. Basic Marxism. In advanced capitalist societies, there are those who own significant quantities of capital and those who do not. The people that do, whether by direct employment or through various intermediaries invest their capital to make a profit, from which they derive an income. The source of profits derives from the labour of others. Capital, collectively, employs a propertyless mass of people (the proletariat) to produce commodities. It doesn't matter whether they're material or "immaterial", the point is the full value of what is produced is not returned to the producer. They have signed up for X quantity of hours in return for a wage or salary. The value realised by the sale of commodities accrues to the employer. Hence this difference - surplus value - is abstract and hidden, and yet can be discerned from the social behaviour of employers and employees. They act as if surplus value is as tangible and real as the sturdy wooden desk my computer rests on.

10. This is where the notion of material interest comes into play. Capital in general is a blind social process. To perpetuate itself (and the owners who depend on it for income) it has to constantly seek new ways of generating greater and greater profits. Seeking markets is one element of this - after all, if no one buys your goods you won't make your money back, let alone see any profit. Where individual capitals exert direct control is in the production process, where it faces the irresistible impetus to drive costs down. Typically this has been via an intensification of the labour process, where the application of technology makes employees more productive - at the cost of little or no extra wages, or by lengthening the working day or reining in pay and benefits. From this standpoint workers are reduced to inputs, to figures winking on a monitor. They are a resource to be managed, or an inconvenience to whittle away. It's not so much a case of Marxism and socialism reducing human beings to proletarians, it's a matter of theory describing a real, concrete process.

11. From the standpoint of capital then, workers are only a means to an end. People are employed to make money. Capital buys labour power for a set number of hours, and that's it. As long as management's right to manage is sacrosanct in its workplaces, it mostly doesn't care what its workers do in their own time. Likewise, despite the best efforts of the media, education, and institutional dictates, we sell our labour power because we have to, not because we want to. And in this relationship, working people too have definite sets of interests. These aren't the result of a thought experiment; struggling around and asserting these interests have had concrete impacts on each and every capitalist society. There's the obvious - capital has an interest in depressing wages, labour has an interest in raising them; capital has an interest in lengthening the working day, labour has an interest in stopping this encroachment on free time. Capital wants its workers subordinated completely to the needs of the business, labour wants the business to fit round their lives. Capital wants to treat its employees like cogs, labour demands to be treated like human beings. This is the stuff of class struggle.

12. The majority of women are dependent on a wage. The majority of men are dependent on a wage. The majority of white people are dependent on a wage. The majority of the global non-white majority are dependent on a wage. Straight people, gay people, bi-people, trans people, the majority of all these are dependent on a wage. Able or disabled; oppressed nationality, oppressor nationality, the one thing they have in common, the experience cutting through the sections and intersections is the experience of the capitalist workplace. Of their subordination to the demands and dictates of capital. You can see why, historically, class has been privileged by labour movements, social democratic parties, and communist parties. So, are we back to the beginning? Is class the lynchpin?

13. Yes. And no. Capital is constituted by struggle. When we sell our labour power, we get caught up in it. There is no escape. But this does not mean everything is "reducible" to class, at least not class narrowly defined in traditional terms. As wage labourers, as proletarians, there is a political economy to how we, as a variegated collection of human beings, reproduce ourselves as such. We reproduce our physical bodies through eating, resting and, yes, actually reproducing; and we reproduce ourselves as social beings in the many varied social contexts that mark our lives as gendered, raced, sexualised people. The former is a physical necessity, the latter is, theoretically, the realm of freedom. It is the space in which we can realise ourselves. We give up chunks of our lives not just to survive, but so we have the resources that allow us to follow our inclinations.

14. The political economy of wage labour, however, is not an idyllic place. The realm of freedom is, too much, a realm of privatised freedom, of seeking comfort in one's peccadilloes before heading back out to the daily grind. The realm of freedom is also potential freedom. Because, for too many people, it's the opposite. Reproducing oneself socially and culturally (and physically) is not a free-floating matter. It is under certain conditions, under the weight of history and convention, and through patterns of certain social institutions. This is the place of the family, the traditional bastion of gender roles, compulsory heterosexuality, and the rule of the father. It is the place of community, of what constitutes an insider and who is coded an outsider. It's the space of the environment, of whether you live in a nice place or a run down estate suffering the effects of crime and pollution. It's the dimension of social and cultural capital, of the networks and status you command - or don't.

15. This is the home, the wellspring of the oppressions addressed by identity politics and intersectionality. As vulgar class politics have treated human beings as wage earners who need to get over their divisions - a critique of the political economy of capital while forgetting/ignoring the political economy of wage labour, you might argue that intersectionality is an attempt to theorise and reconcile the divisions within the political economy of the latter while bracketing the political economy of capital. This is why both have floundered. The former emphasises the simple at the expense of the complex. The latter, the complex at the expense of the simple. The bulk of the proletariat is intersectional. The bulk of the intersectional is proletarian.

16. The separation of the two political economies is an analytical separation. While at work, you might spend your time thinking about the weekend. At the weekend, you might find yourself thinking about work. The values, ideas, prejudices that have taken root outside of the workplace can be and often are carried into the workplace. Capital too has proven adept at using these social divisions - gender, race, sexuality, religion, nationality and status - to help atomise workforces in its ceaseless hunger for more surplus value, more profit. Solidarity is harder to deliver across colour bars and sectarian division.

17. This is where intersectional and class politics, erm, intersect. Exploiting divisions among workers can reinforce divisions among workers. Throwing millions of women out of work after the first and second world wars for the returning men reinforced patriarchy, made them economically dependent on their husbands, and strengthened a strict gendered division of labour in work. Proletarian men benefited - they had their jobs, and, culturally speaking, they were entitled to keep a woman along the lines of the bourgeois home, with its male head and wife/mother. Capital obviously benefited. And women lost out. Privileging either, in this instance, skews the analysis and therefore the political response. Hence, while the two political economies are analytically separate, the struggles in each are tangled up with one another.

18. For those who doubt the salience of class politics, the fact labour movements are growing in the developing world, and have knocked about the advanced capitalist nations just shy of two centuries suggests that doubting is somewhat overstated. Their basic, most basic function, is to bring working people together to face their employers as a disciplined collective. It's far more difficult for capital to pursue its relentless race to the bottom in an organised workplace. Yet in postmodern/identity, and intersectional thinking, labour movements are generally neglected as agents of change. Partly, perhaps, they present as dull and plodding whereas new social movements and their antecedents are fresh, but also because labour movements were occasionally the villains of the piece. Colour bars, gender bars, excluding oppressed nationalities, labour movements at various times and in various places have not only enforced them, but initiated them. This is because then, as now, labour movements are movements of working people as you find them.

19. Yet labour movements have come a long way. They're not perfect. The legacy of gendered and racialised divisions of labour still mark certain sectors of it. Yet, in general terms, they have moved from being a brake on the intersectionality of the working class to facilitating it. What other movement is committed to attacking sexism, racism, homo and transphobia? What other movement throws together people from different faiths and none, actively seeks to recruit resident and immigrant workers, and addresses issues from the workplace to environment, health, economics and quality of life and actively works toward their progressive resolution? There is no other such movement. Except for the labour movement.

20. The solution to intersectionality's quandary, of the theoretical glue that can hold it together, is a fundamentally open socialist politics grounded in the mass, intersectional labour movement that already exists. Class politics, so theorised, also has to reflect the actual intersecting, nuanced practice of the labour movement as it is now. Basically, what's on the table is a merger that's long been established. It's time theory caught up with practice. Struggles around gender, ethnicity and sexuality, and class struggles are part and parcel of the same. Every permutation of identity, the working class is it. And if you look at the other end, when you ask "who benefits?" from intersecting oppression and class exploitation, time after time it's the same group of people - the 1%, the bourgeoisie, the establishment, the power elite, the ruling class.

21. The labour movement is a class movement. It is an intersectional movement. As such it represents a persistent threat to the rule of capital, and, in embryo, speaks of the possibility of a future beyond capitalism. It is a movement articulating the universal interests of the overwhelming majority of people. Get stuck in.

6 comments:

That's very well put, Phil. I would put a somewhat different emphasis on the issue of the labour movement colluding with or and even initiating other forms of discrimination. That can potentially happen, and has certainly happened in the past, but it was a very long time ago. More than a generation back, 40 or 50 years perhaps, certainly in the UK. As you say, the movement reflects workers as they actually are, but the activists and the most conscious layer of members are (often) more or less ahead of changes in social attitudes and consciously try to draw their colleagues along. This is not because they are automatically more progressive or liberal then their workmates, but one of the beauties of the labour movement is its being all about unity and solidarity. Powerful with it, helpless without it. I can remember a time (early 1970's) when many or most workers had some racist views about black workers, but even then they recognised that there had to be solidarity in practice, otherwise the bosses would be gaining the upper hand.

Well said, although one might conclude the concept of intersectionality itself was created by bourgeois sociologists to keep them in a job.

It suits the bourgeoisation of the Left, doesn't it, to award everyone with a chip, and thereby minimise class. Thats what it is really about i think - all the bourgeois Eds and Emilys on the Left were never liked or accepted by the working class so they decided to make new friends.

I should have mentioned this post is indebted to the ideas of Michael Lebowitz in his excellent and must-read book, Beyond Capital.

I have, but can't be arsed to re-state, the same views about "intersectionality" as I expressed last time :)

This is imho the best blog of that stable. I disagree with her views, of course, often intensely so, but still the most (in fact the only) readable one I've encountered.

http://jaythenerdkid.wordpress.com/

Enjoy :)

In 1907 Dan Scully, the Irish American head of the longshoremen's union, testified before the Louisiana legislature:

"You talk about us conspiring with niggers. But let me tell you and your gang, there was a time when I wouldn't even work beside a nigger. You made me work with niggers, eat with niggers, sleep with niggers, drink out of the same water bucket with niggers, and finally got me to the point where if one of them blubbers something about more pay I say "Come on nigger, let's go after the white bastards"

Black, white, gay, straight, male, female what matter? It's working class solidarity that matters and we don't have it in this country the way we used to.

"Intersectionality" is obsessed with what divides us rather than what should unite us.

Sorry to post late. I follow what you have said, and aware that these are naive questions but in point 20, where you say 'the 1%, the bourgeoisie, the establishment, the power elite, the ruling class' implying they are all the same, I get confused.

I am entirely middle class in cultural terms, (I have no ancestor who did manual labour for five generations back), yet for all my 40 years of adult life i have been dependent on a wage.

I could see that this makes me 'working class' in your theoretical analysis, but the implication of your comment and (though you may or may not agree with it), Speedy's comment distinguishing 'bourgeois Ed's and Emily's' from 'the working class', is that this is not so.

It seems odd that I should read what you obviously intend as a call to universality as immediately excluding me. Is this, do you think, more my mistake or yours?

Post a Comment