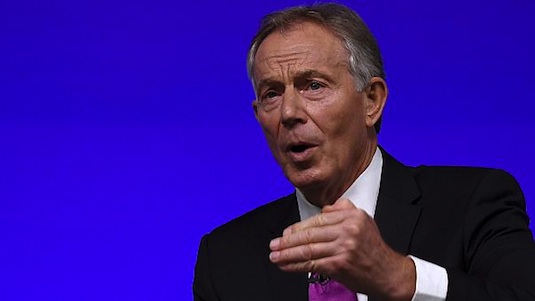

What interests me is the sense that Blair finds Labour's positioning terrible. As someone long wedded to the delusion of technocratic politics and buoyed by the Macron myth, Blair doesn't think a left wing politics in government is possible. He says, "If you’ve got limited time and resources, is nationalisation the priority? If you’ve got £8 billion a year to spend on education, is abolishing rather than reforming tuition fees the right way, or is early years education, particularly for poorer families?" Note that even now, despite a career in front line politics wedded to, yes, a variant of neoliberal politics, Blair cannot bring himself to criticise the putative actions of a Corbyn government politically. It remains couched in terms of "what works", which justified his love-in with PFIs, light touch regulation, and the other nostrums of neoliberal policy and governance we've come to know well.

Then after more chit chat, the interview moves on to Blair's cherished talisman/get out of jail card, the centre ground. He notes that the populist surge is down to the collapse of the "generational promise", the expectation that each generation will do better than its predecessor. There is certainly an an element of truth here, and he recognises centrism has to do better than "trust us, we're the sensibles", though this idea fails to capture the roots of right wing populism. Nevertheless, the place generational promise can be renewed is, yes, in the political centre. He goes on to say with a Labour Party captured by the "hard left" and a Tory Party stained and deranged by Brexit, the centre is frozen out and will find an expression in some way.

He is right, but he is oh so wrong. While there is a mass radicalisation of hundreds of thousands switching on to socialist politics in a way not seen for decades, there are many others who are not but are drawn to Labour simply because the remade party is articulating their interests. Not only are we in tune with the outlook of a rising generation of workers, it is the only one taking their concerns seriously. As former universities minister David Willetts put it, " ... the aspirations of these people – they don’t want a Marxist revolution; they’re not voting for a massive transformation of British society – what they’re wanting, actually, I would argue, is classic Tory aspirations. It’s a property-owning democracy." This presents Corbynism a limit and a challenge if it is to be a truly transformative moment in British politics, though it is assisted - at Willetts's own admission - by a Tory party locked into the older vote. But yes, ultimately these are the aspirations Blairist centrism tried and more or less monopolised before the stock market crash wrecked everything. What Blair doesn't get and cannot compute is the party had to move left to capture them. Pale left-leaning centrism doesn't cut it.

Ultimately, Blair's discombobulation is because his comfort zone doesn't exist any more. Since the war, Parliamentary politics have been dominated by the two big parties, with a cameo of varying duration and influence by the Liberal Democrats and their predecessors. And while there were significant political differences between them there was a continuity of outlooks, of taken for granted assumptions about how the world works and the way government should be run. Before 1979 the Keynesian/welfarist consensus sure a shared approach that was established by the celebrated 1945 Labour administration. After 1979 and particularly following the defeat on the labour movement in the 80s and the shock loss of the 1992 election, it was the Tory-Thatcherite consensus. To all intents and purposes, the three parties were (competing) wings of the same bourgeois party. They protected property rights, they protected profits, they protected the wage relation. With one exception. Labour's politics were on this terrain, but as a party of the labour movement, of the expression of organised proletarians - people who have to sell their ability to labour to earn a living - it was always vulnerable to pressure from below that could potentially threaten the cosy bourgeois consensus. The opening of the 2015 leadership contest and Corbyn's candidacy realised this latent potential. The take over of the Labour Party is the eruption of interests pushed to the margins of official politics, the sorts of interests bourgeois politics want at best want to accommodate and pacify, at worst defeat. That is until they inevitably well up again at another time. What Corbynism means is, as far as ruling class politics go, the party is lost to them. Beyond a few hold outs in the PLP and in town halls, it has put in stark terms the political vulnerability of capital. It's like the red mole clawing its way out of the concrete tomb Thatcherism had imprisoned it in.

Blair and his elite support are paid up members of the ruling class party, albeit the one now utterly marginalised in a Labour Party which, for the first time in its history, is seeing proletarian politics asserted. The dogmatism and bewilderment that has greeted this shattering event, its pathetic expression in the shallow alphabet soup of pro-EU hashtags, the yearning for Macron, the tiresome shenanigans and bad faith briefing, and the totally clueless response of the Tories are the entirely understandable consequence of a politics in crisis, and one not knowing where it's going to end. To nab a line from The Manifesto, for Blairist centrism "all that is holy is profaned, and man is at last compelled to face with sober senses his real conditions of life, and his relations with his kind." And faced with the real state of things, they recoil, invent new fantasies and caress new fetishes - anything but face up to the brute historic fact of their bankruptcy.

Unfortunately, there is a market for advertising one's irrelevance. Blair's niche is less a challenge to Corbynism - he has proven singularly incapable of doing that. But he does offer that most powerful of salves: nostalgia. And I'm quite happy for Blair to pop up every few months with his sage words for the dwindling faithful to lap up. It means he and his are leaving the field clear for us to remake Labour politics in our image and in our interests.

5 comments:

Excellent diatribe against the zombie politics of Blair.

I am, on balance, still a remained but I'm baffled and disturbed in equal measure by some remained welcoming comment from Blair or, more disturbing, Macron.

What is it about the status quo they don't understand as dangerous oxygen for the far right? Remaining in the EU had to come with serious reform we would struggle to get, but it is viewed as messianicly "good" in some quarters. You don't have to look in-depth to be troubled by the prescription on offer, or the people offering it.

"But yes, ultimately these are the aspirations Blairist centrism tried and more or less monopolised before the stock market crash wrecked everything. What Blair doesn't get and cannot compute is the party had to move left to capture them. Pale left-leaning centrism doesn't cut it."

This X 1 million.

In my experience the response to the financial crisis is one of the important Labour fault lines. Either you think it was important and exposed a lot of fundamental issues, or you think it was a severe and unfortunate cyclical event, but it shouldn't alter what Labour was doing pre-crash.

And yet, Phil, Tony’s politics of ‘what works’ will likely impose itself very forcefully on a future Corbyn government.

The significance of neoliberalism is, in part, that it confronted the electoral left with a new class politics of money – a politics that asserted the limits to state intervention and spending in monetary terms. These limits are not as structural and absolute as some have argued. But they do exist when market disciplines are tested, and they express themselves in the form of rising inflation, higher borrowing costs and loss of investor confidence.

This is what is embedded in Tony’s apparently banal (but deeply political) assertion that a future Labour government must be concerned with ‘what works.’

And neoliberalism as a ‘class politics of money’ has been so successful and resilient in large part because the left (including Corbynism) has no critique of money and so no coherent counter-politics of what to do when money – in all its blind and abstract fury – revolts.

It is in the event or threat of money’s revolt that Corbyn’s opponents within Labour expect a return to a version of Tony’s politics of ‘what works.’ They are waging that when confronted with the power and logics of money, the party’s flirtation with proletarian priorities will shatter – aided (as it was before under the 1974-79 Labour government) by the divisive political impact of bringing money’s revolt back under control.

At present, their expectations appear hopelessly – even laughably - outdated and politically irrelevant. I hope they are. But let’s see.

Mike

Interesting points, Mike. Though the fact Labour have already been exploring scenarios of capital flight suggests some lessons have been learned and they're looking at ways of overcoming this sort of disruption in the future. Linked in with this, of course, are the exploration of models of alternative ownership and the rebuilding of the party as a mass movement. After all, the only way to defeat the class politics of money is confront it with a class politics of our own.

Post a Comment