It was a sunny afternoon in March when a group of lecturers, postgrads and ne'er-do-wells descended upon the David Bruce Centre at Keele Uni. The occasion? A paper punctuating the myth of the US morality wars.

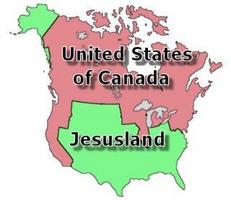

Like many on the revolutionary left I did not support John Kerry's bid for the presidency. Nevertheless when election day went and left George W. in power, I was pretty depressed by the result. Like many others sucked into the media maelstrom surrounding the contest, I bought the line that this was a civil war at the ballot box. Progressives and anyone with common sense would be voting Democrat to get Bush out. On the other hand the evangelicals, the fundamentalists, the gun nuts and the rest were hell bent on rolling back women's rights, gay rights and transforming the USA into some sort of theocracy. It follows that Bush's victory was a victory for the loony right. It implied their reactionary agenda had mass support and that America stood at the threshold of a new medievalist dark age.

According to Prof Chris Bailey, this was not the case. The first question he asked was how abortion and homosexuality specifically came to be regarded as major issues? Bailey pointed to two broad processes: the trajectory of post-war social change has made identity a salient issue for nearly everyone, and as such has spilled over into debates around values; and second, the change in the structures of the two parties have favoured a more participatory democracy where movements can use party platforms to get over their message.

Turning first to social processes, post-war USA (like much of the western world) has seen the frequency of the nuclear family give way to a variety of family forms. The number of marriages fell by half over the 1970-2004 period. The birth rate went into decline, divorces increased, pre-marital cohabitation became more common place and the figures for female-headed households rose. For the traditionalists of the religious right these changes signalled the USA's slide into depravity and hedonism. For progressives they reflected the increasing empowerment of women and US citizens more generally making use of their rights. With such polarised perceptions of change, small wonder the conflict between the camps has been so bitter.

For Bailey the religious right broke with its splendid isolation from politics after the fight for the Equal Rights Amendment gathered momentum after 1971, and particularly the enshrining of abortion as a constitutional right in 1973 in the aftermath of Roe vs Wade. As the evangelicals and fundamentalists believed life begins at conception, to abort a fetus is to kill an innocent. However direct legal challenges on the supreme court decision went no where, so the anti-abortionists changed tack and pursued their objectives through state legislatures. Here their struggle has succeeded in restricting access to abortion by cutting off public funding to clinics, introducing compulsory "counselling", and the requirement to obtain parental or spousal consent, across a number of states. The most ludicrous examples of bureaucratic harassment cited by Bailey is the specification of what chemicals can be used on lawns outside clinics, on pain of closure! Throughout the 80s more states withdrew their funding and at the federal level access was nibbled away by Reagan's appointees to the courts. As it stands today organisations "promoting" abortions overseas were denied federal money in 2001, a federal law against partial birth abortion (an extreme and seldom-practiced method) enacted in 2003, and the passing of the Unborn Victims of Violence Act (where the unborn are legally identified as a US citizen from conception and therefore counted as a muder victim if the mother is murdered), and 32 states refuse to fund abortions. The religious right's guerilla struggle has made some serious advances.

On homosexuality the fundamentalists initially hailed AIDS as divine retribution, and some, including Jerry Falwell, notoriously blamed the attacks of Sept. 11th on lesbians and gays, as well as other familiar targets of the traditionalists. But what really mobilised them were the movement to recognise same sex partnerships, which broke through in 1993 after the Hawaii supreme court decided homosexual couples were entitled to the same protection as heterosexual married couples. The religious right branded the move anti-family and have since been pursuing their attack on gay and lesbian couples through the courts. Again their actions have paid off. The Defense of Marriage Act passed in 1996 defines marriage as a union between a man and woman, and allows states not to recognise same sex unions that have taken place in other states. Also, the federal government may not recognise any same sex union. As of 2006 only Massachusetts allows for same sex marriage and five others recognise forms of union short of marriage whereas 12 ban any kind of recognition. Furthermore 26 states have accepted amendments to their constitutions that defines marriage according to the heterosexual norm.

Undoubtedly these issues generate enormous controversy and can lead to heightened passions. But, argues Bailey, in reality this is only the case for a minority. Despite their prominence in the media and the time devoted to them by mainstream and not-so-mainstream political figures, the morality war is only really between activists and elites from either side. Polling evidence shows that this battle for the soul of America is very much a minority concern. According to his research, only 4% of the sample thought moral questions were the most pressing issues facing the USA today. This is congruent with annual polls produced by Gallup, where the saliency of abortion ranges between 1-8%. This is further backed by a Washington Post poll from last May, where 2% of respondants reportedly voted according to a candidate's views on abortion. Again, a Gallup poll from January 2006 found only 26% of Americans were for overturning Roe vs Wade. Meanwhile, Bailey showed 87% believed LGBT people should have equal employment rights and a plurality favoured adoption by gay and lesbian couples.

These figures demonstrate a lack of polarisation among Americans at large, if anything taken over time Bailey's figures show a growing consensus in the middle ground. Ultimately political elite's concerns with these issues, especially in the Republican party, is a response to the colonisation of the apparatuses by pressure groups. That they are more pliable to the agenda of a tiny minority of Americans underlines how out of touch politicians are with the mainstream.

Perhaps the USA isn't the vast reservoir of reaction we were led to believe it was. Nevertheless, the ease with which the religious right have been able to play the system to attack women's rights and the rights of LGBT people shows how far America has to go before it truly becomes the land of the free.

Like many on the revolutionary left I did not support John Kerry's bid for the presidency. Nevertheless when election day went and left George W. in power, I was pretty depressed by the result. Like many others sucked into the media maelstrom surrounding the contest, I bought the line that this was a civil war at the ballot box. Progressives and anyone with common sense would be voting Democrat to get Bush out. On the other hand the evangelicals, the fundamentalists, the gun nuts and the rest were hell bent on rolling back women's rights, gay rights and transforming the USA into some sort of theocracy. It follows that Bush's victory was a victory for the loony right. It implied their reactionary agenda had mass support and that America stood at the threshold of a new medievalist dark age.

According to Prof Chris Bailey, this was not the case. The first question he asked was how abortion and homosexuality specifically came to be regarded as major issues? Bailey pointed to two broad processes: the trajectory of post-war social change has made identity a salient issue for nearly everyone, and as such has spilled over into debates around values; and second, the change in the structures of the two parties have favoured a more participatory democracy where movements can use party platforms to get over their message.

Turning first to social processes, post-war USA (like much of the western world) has seen the frequency of the nuclear family give way to a variety of family forms. The number of marriages fell by half over the 1970-2004 period. The birth rate went into decline, divorces increased, pre-marital cohabitation became more common place and the figures for female-headed households rose. For the traditionalists of the religious right these changes signalled the USA's slide into depravity and hedonism. For progressives they reflected the increasing empowerment of women and US citizens more generally making use of their rights. With such polarised perceptions of change, small wonder the conflict between the camps has been so bitter.

For Bailey the religious right broke with its splendid isolation from politics after the fight for the Equal Rights Amendment gathered momentum after 1971, and particularly the enshrining of abortion as a constitutional right in 1973 in the aftermath of Roe vs Wade. As the evangelicals and fundamentalists believed life begins at conception, to abort a fetus is to kill an innocent. However direct legal challenges on the supreme court decision went no where, so the anti-abortionists changed tack and pursued their objectives through state legislatures. Here their struggle has succeeded in restricting access to abortion by cutting off public funding to clinics, introducing compulsory "counselling", and the requirement to obtain parental or spousal consent, across a number of states. The most ludicrous examples of bureaucratic harassment cited by Bailey is the specification of what chemicals can be used on lawns outside clinics, on pain of closure! Throughout the 80s more states withdrew their funding and at the federal level access was nibbled away by Reagan's appointees to the courts. As it stands today organisations "promoting" abortions overseas were denied federal money in 2001, a federal law against partial birth abortion (an extreme and seldom-practiced method) enacted in 2003, and the passing of the Unborn Victims of Violence Act (where the unborn are legally identified as a US citizen from conception and therefore counted as a muder victim if the mother is murdered), and 32 states refuse to fund abortions. The religious right's guerilla struggle has made some serious advances.

On homosexuality the fundamentalists initially hailed AIDS as divine retribution, and some, including Jerry Falwell, notoriously blamed the attacks of Sept. 11th on lesbians and gays, as well as other familiar targets of the traditionalists. But what really mobilised them were the movement to recognise same sex partnerships, which broke through in 1993 after the Hawaii supreme court decided homosexual couples were entitled to the same protection as heterosexual married couples. The religious right branded the move anti-family and have since been pursuing their attack on gay and lesbian couples through the courts. Again their actions have paid off. The Defense of Marriage Act passed in 1996 defines marriage as a union between a man and woman, and allows states not to recognise same sex unions that have taken place in other states. Also, the federal government may not recognise any same sex union. As of 2006 only Massachusetts allows for same sex marriage and five others recognise forms of union short of marriage whereas 12 ban any kind of recognition. Furthermore 26 states have accepted amendments to their constitutions that defines marriage according to the heterosexual norm.

Undoubtedly these issues generate enormous controversy and can lead to heightened passions. But, argues Bailey, in reality this is only the case for a minority. Despite their prominence in the media and the time devoted to them by mainstream and not-so-mainstream political figures, the morality war is only really between activists and elites from either side. Polling evidence shows that this battle for the soul of America is very much a minority concern. According to his research, only 4% of the sample thought moral questions were the most pressing issues facing the USA today. This is congruent with annual polls produced by Gallup, where the saliency of abortion ranges between 1-8%. This is further backed by a Washington Post poll from last May, where 2% of respondants reportedly voted according to a candidate's views on abortion. Again, a Gallup poll from January 2006 found only 26% of Americans were for overturning Roe vs Wade. Meanwhile, Bailey showed 87% believed LGBT people should have equal employment rights and a plurality favoured adoption by gay and lesbian couples.

These figures demonstrate a lack of polarisation among Americans at large, if anything taken over time Bailey's figures show a growing consensus in the middle ground. Ultimately political elite's concerns with these issues, especially in the Republican party, is a response to the colonisation of the apparatuses by pressure groups. That they are more pliable to the agenda of a tiny minority of Americans underlines how out of touch politicians are with the mainstream.

Perhaps the USA isn't the vast reservoir of reaction we were led to believe it was. Nevertheless, the ease with which the religious right have been able to play the system to attack women's rights and the rights of LGBT people shows how far America has to go before it truly becomes the land of the free.

3 comments:

Interesting post but there's one thing I would add to the rise of the Christian Right in US politics.

That's the Carter election. He presented himself as a Southern Christian with traditional values and mobilised the Christian Right to support his bid for President.

Once in power it became obvious he didn't have the same vales as the Christian Right on certain issues so they decided to negotiate with the Republians which has contnued to this day.

Good post Phil, I think you are right in saying that the vast majority of Americans aren't all gun-toting, flag waving, god-botherers.

I would suggest that it is only the comfortable middle classes that concern themselves with the moral questions.

I would suggest that with appalling working conditions, the working classes and underclasses are more concerned with keeping their jobs and feeding themselves in an increasingly unequal US society...not that we have anything to shout about here obviously!

Lozza

The Religous left, did a good job for the Democrats in the mid-terms.

Post a Comment