Misogyny. No other word can capture the avalanche of abuse that was heaped upon Caroline Criado-Perez, Stella Creasy, Mary Beard and other women just under a month ago. It was frightening and disturbing. Misogyny, after all, is one of those things official society thought was dealt with in the dim and distant. If women marched and protested in the 1970s, then the Spice Girls and Girl Power in the 1990s signalled women's integration into society as equals. It was done. Women were happy working, raising families, and shopping. Just like men. The rape threats and violent language directed at the aforementioned has forced society into having a conversation it didn't think was needed, and ask why a minority of men work to bully, harass and hound women who do have a public platform.

Growing up at the tail end of the Analogue Age, I didn't go on the Internet until I was 18 and at university. Back then, in the mid-1990s, it was a clunky thing. All you could really do was skip from one website to another, sign up to email lists, join an intentional community or (text-based) role-playing outfit, chat, or, horror of horrors, subscribe to Usenet groups. But for all that it promised something new. It was a digital frontier thinly peopled by a brave few pioneers and homesteaders. At this point, just as hype about the Internet was building in wider culture, cyberspace - a term that barely gets used any more - was a place of hopes and dreams. True, even then there was a moralising undercurrent about the ubiquity of porn, but in the main the emerging internet culture flowed with utopian naivete. The Internet offered disembodied forms of communication where our gendered, colour-coded bodies no longer mattered. We could relate to each other as human beings and not as appendages of the categories society liked to slot us into. It offered a promise where gender, sexuality and race were completely up for redefinition. Or at least went the claims of early philosophers and academic cheerleaders. Digital sociology and cultural studies had a soft job of tracking and reporting on the negotiation and emergence of new identities, new tribes.

The past, as they say, is a foreign country. Reading Laurie Penny's latest book, Cybersexism, I was struck by the very different online lives we had, 10 years apart, at the same age. She writes the Internet "was a place where I could be my 'real' self, rather than the self imposed by the ravening maw of girl-world that seemed to be opening to swallow me up." (p.6) The 10 year difference meant Laurie was maturing when the formerly clear-cut division between online and offline was blurring. More and more, participation in the spaces the Internet afforded required users collapse the distinction between the two. Laurie credits LiveJournal for learning "not just how to write, but how to speak and listen, how to understand my own experience and raise my voice" (p.9). But being online now requires that one comes out of the 'gender closet', and as a woman with something to say, one risks becoming fair game for misogynist attacks. For example, recalling a journo party a couple of years ago she mentions how a young man "in an overstuffed M&S suit" let her know the website he worked for had acquired some photos from her Facebook profile, photos that were of the playful, semi-nude and ever-so-slightly risque kind. They were going to publish them. Why would someone go out of their way to acquire juvenile pictures, and then use them in such a way to threaten, belittle and intimidate if it wasn't about men feeling they had power over a woman?

This is just an example of how patriarchal social relations conspire to keep women in their place. For years, the press and successive governments have warned parents, young women, and girls about the dangers of grooming, of harassment and sexualisation that awaits at the end of a mouse click. There's always a horror story that can be told, or rumours related of slut-shaming websites that will destroy a girl's reputation forever. Social media's dominant platforms - Facebook and Twitter - are technologies of open surveillance. The possibility of being watched, at any time, by a parent, a teacher, a boss, a police officer, or a misogynistic troll is ever present. This is Bentham's Panopticon writ large, the ever-present potential of getting seen and therefore caught out. Hence certain habits are inculcated, a certain conduct becomes the way to behave. And speaking up as a woman about politics and gender, that definitely is not acceptable. In this respect, the new surveillance technologies are a mere extension of the kind of scrutiny women's bodies and behaviour have always attracted. Though, in quite an apposite point, Laurie notes that surveillance technology has brought home to men how they too are now surveilled in the same way.

Naturally, any discussion of cybersexism cannot ignore pornography. Of it, Laurie notes "online misogyny, like any other misogyny, is about power, resentment and frustration, and not about sexual overstimulation, although it can be sexually expressed" (p.16). Therefore Internet porn isn't inherently sexist, though many of the tropes it features are congruent with rape culture. Interestingly, while Laurie rejects differentiating between online and "real" sexuality she notes that the corporates who dominate the web are terrified of allowing porn slip onto its networks. Hence for anyone active with social media and who uses the Internet for sexual activity, there has to be a split between the public-facing performances of self and the other, however that is lived out. Similarly, attempts to regulate the Internet in the name of Protecting Our Children From Sick Filth lets patriarchy off the hook. Banning it, or splitting porn away into a twilight existence prevents a public conversation from developing about sex in the Internet age, and in particular questioning the misogynistic degradation of women in a lot of mainstream het porn. It seems the only "polite" conversation about porn that is permissible is when a performer contracts HIV.

Women therefore are expected to behave in a certain way, and how misogyny can frame women's depiction in porn is taboo - at best it's a private matter, and at worst porn in general is something to crusade against. It is as if Internet culture has drawn a veil over women's behaviour and women's bodies. So when a woman is "unwomanly" enough to draw back that veil and uses a public platform to campaign on something as relatively innocuous as women's representation on banknotes, they're asking for it. The storm of sexist hate that fell on Caroline Criado-Perez's shoulders came as a troubling wake up call for everyone on the left. I had known about instances of misogynistic bullying of women online in the past. Indeed, Laurie herself had previously written about it. But the volume and extremity of the abuse was something else, and I think came as a deep shock to many - women and men both. However, by making itself visible it has galvanised a pro-feminist backlash against it. Bigotry, usually hidden away in whispers or behind closed doors, has come into the open. It has provided a handy focal point to rally against.

The big question, of course, is how to go about it. Cybersexism, though readily identifiable, is a dispersed series of memes, tropes, and attitudes. They are not a series of wrong ideas that can be sorted out by a civilised one-to-one over Skype. Online misogyny is rooted in some (young) men's responses to how masculinity is lived and experienced, in particular the gradual but real erosion of gendered privileges associated with it. Addressing what I understand by a "crisis" of masculinity (and its attendant social pathologies, including this) is beyond the scope of Laurie's book. But the suggestion she does make is, despite not having any illusions in its own problematic relationship to gender and masculinity, the exploration of an alliance between feminism and geek culture. In general, geek culture does value personal autonomy and freedom from censorship. If it can be shown that those values are shared values, and that cybersexism presents a fundamental threat to them then feminists might have a powerful ally that can root out misogyny. After all, Anonymous has form unmasking hate pedlars, such as this charmer.

Cybersexism is a short book packed with insights about the recoding of gender in the digital age, up to and including male privilege, rape culture, and trophy wife syndrome. It's also a book about women's appreciation of the opportunities the Internet offers and how patriarchy's misogynist excrescences tries to deny them to half of the population. And as well as all of these, it's a call to arms. Laurie's is an important contribution to the 'new' feminism, and stands every chance of becoming an influential one.

Image credit

I'm well aware it's supposed to be *M.O.R.P.H.*. And yes, the video is awful. But An Angel's Love is a truly beautiful track, though as a trance purist I prefer the extended vocal mix to below's radio edit.

I just want to make some points about this article by Joe Rivers that appeared on the New Statesman website today.

1. Despite its title, 'Let's stop pretending internet activism is a real thing', it's not really about that at all. I can only assume it was subbed with that heading to pick up a few Facebook likes and retweets on what is traditionally a slow day for all bloggers. But the idea the internet and social media particularly offers a facsimile of activism is absolutely nothing new. Remember 2009's battle for the Christmas Number One? An internet-based grassroots movement managed to send Rage Against the Machine's Killing in the Name of to the top spot at the expense of that year's long-forgotten X-Factor clone. Hardly up there with the storming of the Winter Palace, it still captured the imagination of thousands who indulged this foray into subversive shopping. It was a simulacrum of activism. But even at the end of the last decade this sort of activity was old hat. Go back to the initial wave of activist uses of the internet in the 1990s and you will find plenty for whom Usenet debates were a substitute for activity.

2. Internet activism is a 'real thing' when it is part of what one does as an activist. Joe demonstrates this quite well with how social media has facilitated the coming together of a new wave of feminist activism. It certainly has proponents and detractors who prefer to fight for women in 140 characters or less, but it is a movement mobilising and inspiring tens of thousands around all kinds of activities and, of course, it is one that has proved both media savvy and media friendly. Speaking personally, when not treating lucky readers to my fantastic taste in music this blog is about producing a critical understanding of the world and pushing labour movement politics and activism. I only tend to respect those bloggers, writers and Twitter celebs who engage with the world beyond their monitor screen, because I do. And if I and many, many others can there's no excuse for those the internet has provided a large audience not to get down and dirty with campaigning.

3. Joe says there's "not enough" activism. Sure, we could always do with more people doing stuff. After all, as much as our honourable members pay lip service to the idea the one thing most of them dread is an active and critical citizenry. However, a lot of what does go on just doesn't get media coverage. The campaign to save Stafford Hospital did get press and TV slots because of the high profile failure of its management and the tragic consequences they entailed. Yet while that was (and is) going on, dozens of other groups have mushroomed to defend service provision at their hospitals. Likewise saving children's centres, participation in community asset transfers, running food banks, protesting closures, strikes and solidarity activity, organising residents' associations, all this sort of unglamorous stuff flies right under the national media's radar because, for whatever reason, they don't find it interesting. For example, how many reports have you read flagging up tonight's mass sleep out protest against the bedroom tax?

4. Joe rightly notes turn out in general elections looks to be on the up. Likewise, young people are more interested in politics than they were a decade ago, at least according to this study from 2011. Furthermore there is a core of the UK's adult population - some 36% of people - who are responsible for just shy of 90% of all volunteering activity. A sizeable minority are far from "apathetic" and actively contribute to the country's civic life in some way.

5. His point that there is too much 'anti' stuff is true. But is this symptomatic of a diminution in the "quality" of protest and social movements in Britain? I don't think so. In the era of rapacious and aggressive capital inaugurated by Thatcher's election in 1979 most, if not all the big struggles have been defensive and therefore anti-something. The Miners. Wapping. CND and Greenham Common. The Poll Tax. Iraq. Tuition Fees. All key moments in the modern history of protest, all of them defensive. Social movements are always conditioned by the opportunities afforded them by the wider environment, and the circumstances that threw them together. To pass from defensive into offensive, or positive struggles requires that they are occasionally successful and 'win', and that there is something that can condense these victories and integrate them into a wider (political) programme.

6. You can moan about inadequate rates of political and civic participation until the cows come home. The real challenge, the proper test of anyone's mettle is actually doing something about it.

The BBC is beholden to an agenda that is anti-British, pro-union, and left-wing. Or so the argument goes. Thing is, there's no evidence for it. Back in November, I had a bit of fun asking if the BBC's Question Time was biased. This little study, based on the political allegiances of guests appearing on the programme between December 2008 and November 2012 found there was bias - the number of rightwing panelists outweighed guests from the left. Now a group of academics at Cardiff University have performed a wider content analysis. Funded by the BBC itself, it wanted to know how impartial its reporting really was.

Guess what? This report based on actual, real evidence and not ideas plucked from the hot air of a rightwing dinner party, found there was no leftwing bias. Yet again, coverage was tilted to the right.

For example,

Among political sources, Labour and Conservatives dominate coverage accounting for 86% of source appearances in 2007 and 79.7% in 2012. Our data also show that Conservatives get more airtime than Labour. Bearing in mind that incumbents always receive more coverage than opposition politicians, the ratio was much more pronounced when the Conservatives were in power in 2012.

In strand one (reporting of immigration, the EU and religion), Gordon Brown outnumbered David Cameron in appearances by a ratio of less than two to one (47 vs 26) in 2007. In 2012 David Cameron outnumbered Ed Milliband by a factor of nearly four to one (53 vs 15). Labour cabinet members and ministers outnumbered Conservative shadow cabinet and ministers by approximately two to one (90 vs 46) in 2007; in 2012, Conservative cabinet members and ministers outnumbered their Labour counterparts by more than four to one (67 to 15).

In strand two (reporting of all topics) Conservative politicians were featured more than 50% more often than Labour ones (24 vs 15) across the two time periods on the BBC News at Six. So the evidence is clear that BBC does not lean to the left it actually provides more space for Conservative voices.

The observations made in my small examination of Question Time appearances are borne out by the systematic study of BBC output.

Yes, sure, a foam flecked Tory will be able to find reports that are critical of the government's record, or an occasional item on the EU in which it is not denounced as the USSR's second coming. But facts are stubborn things. The numbers show the BBC is a big C Conservative institution.

Two articles. Two broadly similar points. In the first place is James Bloodsworth's piece for the New Statesman that makes what should be an uncontroversial observation: that "backward" attitudes among working class people toward immigration and social security stems from competition with and close social proximity to migrants and recipients of the dole. Hell's bells, even someone as unoriginal as me has occasionally made the same points. Perhaps it is symptomatic of the estrangement James talks about that his piece was shared widely on social media. Unfortunately, the bleeding obvious does need restating at times.

The second comes from the professional contrarians of the former Revolutionary Communist Party. Mick Hume argues that Ed Miliband is vacuous, and that's okay because it fits nice with the void in Labour's shell. Social democracy is dead, Labour is rotting on its feet, etc. etc. When RCP cadre weren't trying to horizontally recruit young people in the late 80s, it used to push the same line then - but with the certainty that Labour's demise would lead to its immediate replacement by the RCP itself. All that's different 25 years on is while their position was previously trumpeted with revolutionary enthusiasm, it's now muttered with all the cynicism a defeated and unlamented project can summon.

An aside - the RCP apparently went one better than Lenin and said Capital could only be understood if read in the original German. I doubt leading figures took their own advice, because Mick Hume's piece reeks of fatalism and hopelessness.

The majority of the left and the pontificariat, like Spiked, are aware that British capitalism has undergone seismic changes. The particular kind of working class politics that grew up under the 1945-79 settlement had to be - and were - brutally broken up in the 1980s. The neoliberal model of mass privatisation, offshoring of jobs, vocationalisation of education, and "hands off" economic policy met its Waterloo in 2008. What kind of capitalism comes next is still up in the air, though it's becoming increasingly clear what Labour's "offer" will look like.

During this period, along with the restructuring of British capitalism the working class has changed. The labour movement has declined in absolute numbers by about half and trade union density in a larger work force is the even more worrying story. The communities of solidarity that grew up around one or two industries are largely gone. Class, as an active means of identifying oneself, is seldom seen outside of the chest-beating nonsense of the far left. Employment and consumerist practices, often by design, serve to individuate, not collectivise. And the big collective struggles of the last 30 years - the miners in the 80s, the anti-war movement in the 00s, failed. In short, the working class exists. But it ain't what it used to be.

One of the consequences of the defeat and dispersal of working class solidarities is the impact it had had on the Labour Party. Forget the fairy tales you may have heard about Labour's socialist golden age, it has never been anything but a social democratic party. Just as trade unions exist to represent and stand up for working people in the capitalist workplace, so Labour has, at best, stood up for the interests of working people in the context of British capitalism. So next time you hear someone moaning about Labour being an "openly pro-capitalist party" you have to ask yourself who really has or had "illusions in Labour". Nevertheless, as the labour movement has weakened the transmission belt provided by the trade unions and community organisations that fed the party generations of working class politicians narrowed and, in some places, were choked off. The progressive middle class element as exemplified by Blair seized their moment and New Labour was born. The redundancy of industrial working class political signifiers were actively dumped as unnecessary baggage, as relics that would only ever get in the way of winning elections. And true enough, for its part New Labour's authoritarian mangerialism was deeply alienating. For instance you don't want MPs speaking like human resource officers, especially when you had to hear that crap at work. So while New Labour was a symptom of labour movement decline, it compounded it through high handedness, active disassociation from working people, and a policy agenda that was deeply problematic from a labour movement point of view.

And yet, despite this, Labour's relationship to the labour movement remained intact. The much-vaunted Labour link is more than a bureaucratic arrangement beneficial to apparatchiks in party and movement, it's a real connection that exists at all levels. The stated political allegiances of active trade unionists tends to be Labour. And, funnily enough, local constituency parties tend to have quite a few union members at their monthly meetings too. But where trade unions have been unsuccessful - as the Falkirk debacle demonstrated - is organising effectively in the party to promote the kinds of policies and people that can make the link work.

Like many of his ilk, Mick Hume cannot see outside the Westminster bubble. His pitiful piece is a retread of every criticism ventured in this most snarky of silly seasons, albeit with the sprinkling of chic particular to his brand of radical spectating.

But the fact that Labour still has a clear, organic relationship to the class that founded it is not cause for sitting on our laurels. Speaking the language of class today is more difficult because 'our people' are more differentiated than ever before, but they know crap wages and job insecurity well enough. They too know about declining incomes and rising prices better than any policy wonk. For Labour to succeed, to "reconnect" with millions more speaking to working people's actual experiences is what we need to be doing more of. And if we are returned to power in 2015, implementing policies that address these problems would go some way to building up the constituency, the head of steam, that can drive Labour to deeper and more radical changes in the decade beyond.

Brain block tonight, blog-chums. So how's this for a piece of political artistry? Unfortunately, I don't know who to credit it to. Anyone know?

Post script: Thanks to Chris in the comments. Image source

This from John Goldthorpe's On Sociology. I think it works as a pithy summary of what was at stake during the postmodern detour much social theory took from the late 80s to more recent times.

[Western rationalism supposes] that a world exists 'out there', independently of the ideas about it that any particular scholar or scientist may hold; that it is possible to use language in order to make statements about this world that may be regarded as being true in the degree to which they accurately represent or 'correspond to' it; and that the attempt to determine their truth, or otherwise, can be carried out through various procedures grounded in a generally valid logic governing the linkage of evidence and argument ...

[Postmodernism argues] there is no world 'out there' existing independently of our representations of it, or, that is of the ways in which we socially construct it through our language; thus, the criterion of the truth of statements cannot be correspondence with such an independent world; truth is not discovered but it is rather made, and is made, moreover, on many different ways, and always with a moral and political intent; thus all truth is 'local' and 'contextual'; there is no knowledge that can claim a privileged, objective, and universal status by virtue of the methods through which it is secured, only 'knowledges' that are specific to particular communities, cultures, and so on, and that serve their purposes." (2000, p.8)

Plenty of food for thought in there I might return to in due course.

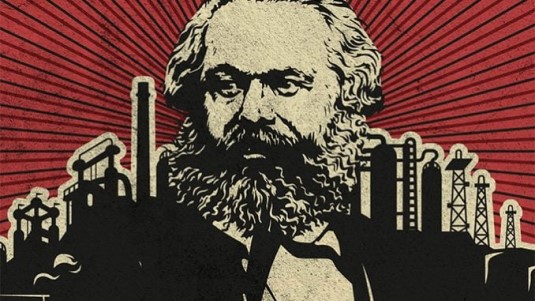

If you're not a lefty geek you probably don't know a literature has grown up around scattered remarks by Marx on the 'D' word - dialectics. There, I said it. Listen carefully and you might hear half the audience clicking their mouse button to navigate away. And who can blame them? Dialectics have a terrible reputation, not least because they are abused to bolster a bit of dirge with some clever-sounding terminology, provide a posse of get out clauses should otherwise cast-iron prophecies not come to pass, or to position oneself as an adroit thinker and masterful interpreter of the grey beards without saying a great deal. I think it was Heidegger who observed that legibility would mean the death of philosophy, and that applies equally to those who set themselves up as gatekeepers to the Marxist screed. And as for academic commentaries, if anything they are much worse.

When I was first learning about Marx and Marxism dialectics appeared to me as reified, impenetrable things, a matter far from helped by Lenin's injunction (in private notes) that you needed to read and understand Hegel's Science of Logic if you were to ever get a handle on Capital. But I was determined to get my head round them because its proponents held out the promise of their being master keys that could unlock the secrets of social phenomena (and nature, if you followed crude and uncritical celebrations of Engels' Dialectics of Nature). Undaunted, I vowed to make use of a protracted period of unemployment by burrowing into Marx and the mountain of commentary grown up around him. As you would expect most of the stuff I read at that time was opaque. I gave up on CLR James's Notes on Dialectics - a reading that took Lenin's dictum seriously and ploughed straight into Hegel. I had a tough time with Maurice Cornforth's Materialism and the Dialectical Method and the four-volume Issues in Marxist Philosophy, but I got a handle on the core precepts of the dialectical method eventually. After much obfuscation and outright bullshit, it basically boils down to the observation that social relations are interconnected, conflict with one another, and are forever in a process of change.

What's brought this trip down memory lane on? I've recently been toying with the idea of revisiting Capital and actually finish it this time round. Third time lucky, perhaps. The passage below stood out as some of the most beguiling Marx ever wrote, not least because he avoided writing a treatise on his dialectics. So what is his basic position?

For Hegel, the process of thinking ... is the creator of the real world, and the real world is only the external appearance of 'the idea'. With me the reverse is true: the ideal is nothing but the material world reflected in the mind of man, and translated into forms of thought ... The mystification the dialectic suffers in Hegel's hands by no means prevents him from being the first to present its general forms of motion in a comprehensive and conscious manner. With him it is standing on its head, It must be inverted, in order to discover the rational kernel within the mystical shell. In its mystified form, the dialectic became the fashion in Germany, because it seemed to transfigure and glorify what exists. In its rational form it is a scandal and an abomination to the bourgeoisie and its doctrinaire spokesmen, because it includes in its positive understanding of what exists a simultaneous recognition of its negation, its inevitable destruction: because it regards every historically developed form as being in a fluid state, in motion and therefore it grasps its transient aspect as well; because it does not let itself be impressed by anything, being in its essence critical and revolutionary. (1968, pp102-3)

A quick note on terminology. 'The dialectic' or 'dialectics' implies something otherworldly, or a mystifying plurality that denotes nothing but itself. In Marx's hands it/they are neither of these. It is simply a name denoting the simultaneity of interconnectedness, conflict and change.

What does turning Hegel the right way up entail, and what's so frightful about it? As Marx notes, for Hegel the world as it was and will be is the reflection of 'the idea', or reason, or the 'absolute' unfolding and coming into being through the history of our species. Each epoch in history, from antiquity to the moment Hegel was writing constituted a moment in the progress of the idea becoming conscious of itself. But, and this point is often overlooked, this was not a linear process. History unconsciously, semi-consciously, and then fully consciously gropes toward reason through dialectical processes. History - with a capital H - approaches reason through innumerable contradictions that are resolved, but also seed subsequent History with the elements of new conflicts. Over time, the scope of these contradictions narrow to the point where the End of History is reached and human history, as we understand it, stops and we live in a new age governed by reason. As far as Hegel was concerned, as he grew more crotchety and conservative with age he came to identify the Prussian state with the idea - a misrecognition only surpassed by Francis Fukuyama's pronouncement that the End of History had come with the fall of the Berlin Wall. But nonetheless, for Marx Hegel's great achievement was that he had, in the abstract through his dialectics captured the 'shape' and the 'movement' of social processes in a particular kind of society and a certain historical conjuncture. Behind the foreboding language of the passage of quantity into quality, interpenetration of opposites and the negation of the negation lay a dynamic appreciation of how social relations are constituted, develop and dissipate.

Whereas in Hegel it was the idea that drove dialectics, putting him the right way up demonstrates it was actually dialectics that drove the development - or allowed for the very possibility - of the idea. In Hegel's hands, dialectical philosophy justified the status quo with its appeal to revealed reason. But in Marx's hands it became a weapon for the deepest, most thoroughgoing understanding and critique of human societies. For Marx, who had no time for deities or phantoms (except as handy metaphors), all of human history and prehistory was a material process of dialectical interaction with the natural world. All of our achievements and continued viability as a species rests on the productive relationship with have with the world around us. With the concomitant development of agriculture and civilisation, history (with a small h) effectively began when early societies were consistently able to produce a surplus over and above the needs of those communities. Struggles over the disposal of that surplus sedimented into different classes. Who controlled a society's material resources have, since about 5,000 years ago, been a question of class. Since then different kinds of class societies have come and gone, the playing out of class antagonisms and contradictions largely conditioning the shape of the kind of society that came after. For instance, as the feudal relationships between lord and serf decayed in mediaeval England the contradictions arising from the contradictions between them, the nascent merchant classes in the towns, and large numbers of landless labourers saw traditional relationships in the countryside displaced by a mercantile one whereby labour power was given in exchange for a wage, and produce was grown and sold primarily for profit. As the profit motive and the drive to accumulate in competition against others spread and subsumed all productive activity, so the material impulse to innovate - which seldom existed outside of warfare - entered into economics and gave us capitalism, the first truly dynamic social system.

Therefore all of human history for Marx is merely a succession of material struggles, and ideas - such as those of Hegels - are more or less abstract representations of contending clashes of interests. Hence the term materialist dialectics or (if you must) dialectical materialism. Their abominable quality, as Marx noted, lies in the simple observation that nothing is eternal. The rule of the most benign forms of capital rests on the exploitation of one class by another, and sooner or later the class contradictions contained within capitalist social formations shall resolve themselves. They can do so positively in the emergence of a new society in which the economic exploitation of one human being by another is consigned to history, or negatively in some other, so far unanticipated system of class rule with its own set of dynamics, contradictions and possibilities.

The point is that dialectics are utterly straightforward to the point of banality, and indeed would be if they did not have serious political implications for whatever happens to be the ruling state of affairs.

NB This old post on the place of abstraction in Marx's dialectical method might prove interesting to some.

Life must be tough for the Daily and Sunday Express. Before this weekend's news that police are looking at "new information" concerning the death of Princess Diana, this august organ of moral rectitude hadn't run with a Diana-related story since Thursday. One whole day without their idol. It must have been hell trying to find different fodder to throw at their ever-shrinking readership. Of course, the new angle to the interminable whirlwind of conspiracy and rumour turning about her untimely demise is grist to the Express's mill. A whole edifice of conjecture will be piled on top of the short, terse statement released by the Metropolitan Police. After all, why splash out on properly investigated journalism when the cost of new stories can be reduced to that of an internet connection?

I have to say, I've never cared for the conspiracy-mongering around Princess Diana's case because I believe it, like nearly every single conspiracy theory in the round, is bunk. Nor do I share a forelock-tugging fascination for the Royals. My interest, if it can be described as such, extends to the role they play in British culture, politics and its constitutional set up. It would therefore be remiss of any socialist to file them away in a cabinet marked 'ignore'. But last night when the story broke, and after BBC4's latest Scandinavian crime import, we did have a bit of fun with the conspiracy.

If it turned out that The Star's headline is true, and the People's Princess was indeed killed by the military or a section of the secret services in cahoots with establishment figures, could you imagine the huge crisis of legitimacy the British state would face? And if the trail led all the way to Buckingham Palace, as Mohammed Al-Fayed has consistently maintained, we could have a republic by Christmas. The only problem then would be what comes next. Dave, as the all-powerful Prime Minister might recommend a ceremonial presidency while the real power remains concentrated in his office. And who among the Conservatives would likely go for it? Boris Johnson for President?

A case of being careful what you wish for, perhaps.

Given the thoroughness of the enquiries into Diana's death, I am pretty certain that whatever allegations the Met are looking into will not have any bearing on the settled decision. Not that this matters. While alive Diana encapsulated in her person all the glamour and celebrity one would expect a fairytale princess to have. A solid blue blood by any reckoning, through her charity work and helped by a sympathetic press she was able to cultivate a common touch or, at least, the popular perception of having one. And credit where it's due, Diana used her celebrity to dispel myths around HIV/AIDS via repeated photo opps and awareness raising campaigns. In short, she was distant and yet very close, she was other worldly but genuinely cared for the ill and the vulnerable. This in the time before the internet took off, she was as ubiquitous a personality as one could be in the print/analogue age.

Diana was also something of an insurgent royal. Cast out by scandal and divorce Diana's popularity eclipsed that of every other member of the House of Windsor. Only the Queen Mother, the nation's granny, came close. So her death in a Parisian tunnel was a shock. Not just for those who identified with her in some way, but for the entirety of British culture. She was a fixture of our heavily mediatised every-day and in the weeks after her death, genuine outpourings of grief were reinforced and amplified by non-stop media coverage of her death. Sporting events were cancelled "in respect", press and TV schedules were rammed with tributes. So powerful, so pervasive was the contrived climate of mourning that the death of Mother Theresa of Calcutta - a noted and celebrated "living saint" for her (problematic) work among the poor - passed with nary a comment. I don't think Britain had seen anything like the reaction Diana's death wrought, and I don't think it will ever be seen again either.

The rise and demise of Princess Diana was a singular event made possible by the media's political economy at that time. As such it left a deep impression on the country's cultural memory. If you lived through it, you have your own memories of it. And for some, for those millions who look to the Royal Family as a rock of stability in a society undergoing constant, profound, strange and unsettling social change the passing of Diana made a lasting mark on their outlook. For them, Diana's death was a cruel reminder that nothing lasts forever. Hence The Express functions as a crutch mitigating this pain by almost daily turning over its pages to nostalgia, and reminding its readers that the glamour and the good works are now shouldered by William, Kate and Harry.

Almost 16 years after her death, unfortunately, there are many people all too willing to still buy into Diana's personality cult. And should some new, troubling light be cast upon the circumstances surrounding the crash in that Parisian tunnel it is one that will get a new lease of life.