Cameron was the toast of the town as far as the liberal press were concerned. There were some voices raised about the recklessness of risking something as important as the UK's economic wellbeing for a prize so paltry, but this was largely ignored as centrist columnist and Labour backbencher spoke up to congratulate him for seeing us through the referendum. For the time being, the Tory right and their UKIP outriders were quiet and stunned into silence. The attention, however, swiftly moved to the Labour Party. While welcoming the outcome of the referendum, Jeremy Corbyn was roundly attacked by his backbenchers for offering "lacklustre leadership" and refusing to campaign alongside the Prime Minister to keep Britain in. Rumours of a move to depose the Labour leader did the rounds, and then went into action. On the following Monday, shadow minister after shadow minister lined up to resign, with some timing their departures to meet the hourly headlines on BBC News and Sky News. And then, that evening, Margaret Hodge tabled a motion of no confidence in Corbyn at the PLP's weekly meeting. It easily carried by 172 votes to 40, but the embattled Labour leader said this had no constitutional legitimacy and he would carry on after 60% of members had put their trust in him. Unfortunately for Labour, the crisis continued which, eventually, saw the little known South Wales MP and DWP shadow Owen Smith emerge as a challenger. As the party turned in on itself, Cameron's star rose even higher and Tory party polling received a renewed boost as he affected a statesmanlike gait vs the unseemly rabble across the Commons.

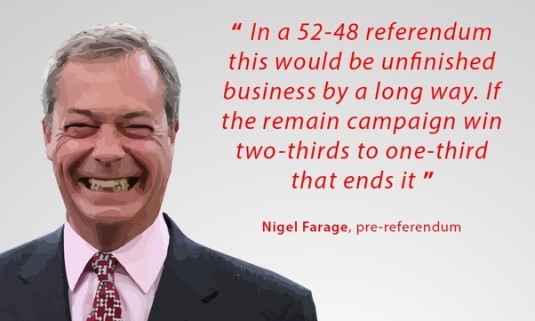

It wasn't long before matters started slipping for the Tories. In the first weekend after the referendum, a small crowd of Leave supporters held a rally in Trafalgar Square protesting the referendum con job. This weekly occurrence, not always in the same location, received little coverage and got scraps of notice in the press, but following the shock victory of Donald Trump in November's US Presidential election they became increasingly emboldened. Nigel Farage, forgetting earlier remarks where he promised to stand down as UKIP's leader began addressing the weekly rallies. They grew and, as the glow faded from the Prime Minister's referendum victory, he started looking increasingly vulnerable to backbench rebellion. The complaints about government spending and "dirty tricks" Farage raised on referendum night started coming back. The Daily Express ran lurid tales of public sector employers expecting their staff to vote remain, while acres' worth of articles complained about how the government flouted its own rules on campaigning spend. It wasn't long before the legitimacy of the referendum result was questioned - first by UKIP, but then increasingly by Tory backbenchers out of sorts in the renewed Kingdom of Dave.

For the moment, there were few opportunities for putative rebels to flex their muscles. When the Commons resumed in the Autumn following Jeremy Corbyn's second emphatic leadership victory, legislation due for introduction into the House was, for a rebellion-minded Tory malcontent, uncontentious. Likewise the obvious successors to Dave were very much bound close to him. George Osborne carried on in Number 11, and Theresa May remained at the Home Office where she'd been since 2010. A new addition to the cabinet was Boris Johnson, rewarded with the Foreign Secretary post for playing a leading role in the remain campaign, a position consistent with his pro-EU journalistic outpourings in recent years. The right inside and outside of the party might have been getting restless, but so far Cameron was shielded and the slow roll out of manifesto promises, such as a new (and punitive) Youth Allowance scheme designed to replace the dole for 18-21 year olds, the £10bn "war on waste" (a new programme of public sector cuts as opposed to an initiative aimed at curbing Britain's growing refuse problem), and extending the Free School programme further gave internal Tory opposition few opportunities to make strides.

And then, trouble. In December Jamie Reed, the Labour MP for Copeland announced he was resigning his seat. This was followed in early January by Stoke Central's MP, Tristram Hunt. Both were well-known critics of Corbyn, but had decided to pursue careers outside of Parliament instead. The contest in Stoke immediately captured the attention of the London-based media. As the city had an inglorious recent track record of returning far right councillors and, during the referendum, had voted by a large margin to Leave (Stoke Central itself was 62%/38%), this seemed like ripe territory for a UKIP challenge at the subsequent by-election. Having been burned so many times by failures at the polls, Farage was reluctant to stand but after some dithering was confirmed as the party's candidate in the by-election. For six weeks the media circus descended on Stoke-on-Trent. Activists from across the country poured in to help Labour's Gareth Snell retain the seat, and the campaign was very close. As the early hours of 24th February came in, first the awful news Labour had lost Copeland to the Tories, but then the shattering chaser. Mobilising the constituency's Leave discontent, Labour's vote held up but a collapse in Conservative support saw Farage squeeze home with a 800 vote majority. The scenario Cameron dreaded the most had come to pass: he would now face occasional questions in the Commons from the UKIP leader.

This plunged Labour into further crisis, with claims about Corbyn's incompetence doing the rounds and crisis talks over whether the party was doomed in its former working class heartlands. Even some leftwingers took to print to raise doubts about Corbyn's suitability. However, the momentum was with UKIP and while Labour looked inwards it was on the right where the effects of the by-election triumph were most felt. On entering the Commons Farage was welcomed by a rally of several thousand elderly leavers, and a march the following weekend saw 20,000 take to the capital's streets. Not a big demonstration by the standards of the left, it commanded disproportionate media attention with senior BBC and ITV journalists dipping in and out of the crowd. And then when the excitable "people's army" descended on Hyde Park to hear the words of Nigel Farage MP, they were driven to ribbons of ecstasy as he denounced the fraud perpetuated on the British people and raised a new rallying cry. The first referendum was deeply flawed, unfair, and distorted by the liberal elites who set it: it was time for an unsullied People's Referendum. Matters were not helped when, it emerged weeks later, Farage had been having regular meetings with the European Research Group faction of backbench MPs, and had even spoken at one of their gatherings. The press could smell trouble brewing and captivated by the splash Farage had made in the Commons, attention switched away from Labour's difficulties. Matters came to ahead over Osborne's Budget speech. Having learned from his second omnishambles budget of the previous year, he tried keeping matters on an even keel. Strong GDP data helped by renewed investment, following a brief pause while business awaited the referendum's outcome, meant increased tax receipts and so, Osborne argued, more room to raise the basic tax threshold even higher. However, when earlier drafts of his chancellor's speech leaked it was revealed this was initially going to be dubbed the Remain Dividend. The fact Osborne never used the phrase didn't matter. He was harangued by The Mail and The Express for lording it over the leavers, and (anonymous) Tory MPs made sure the press were well briefed about their outrage. It looked like the Tories were going to tear themselves apart.

As it happened, the next big shock struck at the very heart of the Tory programme. On 14th June fire crews were called to a fire at Grenfell Tower, which quickly burned out of all control. The blaze killed 72 residents and made hundreds more homeless. It quickly transpired the local Conservative council had cut corners on the external cladding and it did not meet fire safety requirements - all for the sake of a saving of a few thousand pounds. Immediately, Labour's internal distractions fell away and Jeremy Corbyn connected the tragedy to Cameron's and Osborne's austerity measures. Within days Corbyn was out meeting the families and speaking with the community, whereas the chancellor completely went to ground while Cameron was on an overseas trip. Caught flat footed, it eventually fell to Boris Johnson, as former London mayor, to do the official walkabout - though even he failed to meet with the families. This appalling spectacle, rightly perceived as callous and uncaring, hit the Tories hard. Already suffering thanks to UKIP's sustained 15-20% in the polls, for the first time under Corbyn Labour moved into the lead. Sensing an opportunity to embarrass the government into backtracking on cuts, Corbyn launched a nationwide tour with Grenfell community representatives. The PLP were not too happy, but by all accounts the programme of events were a success, with large crowds turning up to hear him put the anti-austerity message. Keen not to miss a bandwagon, Farage and UKIP discovered they were an anti-austerity party and said for too long the posh liberal Tory elite had balanced the books on the backs of the poor. Squeezed from two directions, Cameron was in a difficult place.

Another unhappy circumstance of the Remain victory was the fact subsequent EU meetings attended by Cameron were subject to the keenest, and some might say hysterical press scrutiny. The "renegotiations" he had undertaken prior to calling the referendum turned out to be cosmetic changes. The right wing press gleefully seized on EU migration figures, and beggar-thy-neighbour stories about EU citizens claiming benefits and "health tourism", which continued to aggravate the steadily diminishing newspaper audiences. Every time the EU agreed something which Cameron simply accepted, this was more proof of Britain's betrayal by its leaders. And when Cameron had to report on matters European in the Commons invariably the Speaker John Bercow would impishly allow Farage to ask a question.

By early 2018, Cameron had had enough. The feeling of being trapped by his backbenchers, of wincing at the UKIP thorn in his side and now, facing an energised and confident Corbyn in the Commons, was by no means guaranteed to "win" each week at Prime Minister's Questions. Following what was to be Osborne's final budget, which begrudgingly released funds for the safe recladding of Britain's public housing tower blocks, he announced the timetable of his departure as per the promise he made prior to 2015. Suggesting the Conservative Party had some hard choices ahead, he fired the starting gun on the contest so the party had the summer to debate and regroup. In the first round, the expected big beasts in the form of Johnson and May declared their intentions, but as always a few no-hopers wanting a bit of recognition stuck their names in. Sajid Javid, Dominic Raab, and Andrea Leadsom tipped their hands from the right, while the relatively unknown Rory Stewart pitched in from the party's centre. Interestingly, Osborne didn't contest - divining correctly someone who is virtually the ancien regime wouldn't stand a chance. Michael Gove, exiled to the backbenchers since heading up the Leave campaign, also put himself forward and established himself as the most credible Leave adjacent voice - and the potential leader most able to see off UKIP. For her part, May won plaudits for talking about social justice and rediscovering a Tory sense of responsibility to those at society's sharpest end. To hear one nation rhetoric not entirely dissimilar to the arguments made by Ed Miliband a few years previously turned heads and captured a great deal of broadcast and liberal press coverage. Johnson, for his part, must have been left wondering if stumping for Remain was the right career move. Popular in the party for his jovial bon homie, unfortunately for him there was little to offer. He claimed to be an election winner who could take on the left, but on matters of policy he was either vague or sounded like he was copying May. And he promised to stand up to Brussels, but given his role in the referendum Gove had greater credibility on this score.

In the end, Johnson was squeezed out by the rounds of voting and Gove and May went to the membership. The election was a strange affair, with May successfully avoiding public face-to-face debates with Gove. This allowed her to set out her stall as a reluctant remainer who treasured the sovereignty of the UK, but on balance believed staying in the EU was the right thing - but that the government should take tougher stances versus Brussels and seek to reopen negotiations on the terms of membership. Gove was able to easily outflank this from the right, and hinted on more than once occasion that perhaps UKIP and the second referendum campaign had a point. However, on matters of wider policy Gove praised Cameron and Osborne and stated in no uncertain terms he would more or less offer the same. May on the other hand seemed to take the threat from Labour seriously, who were leading in the polls despite an outbreak of infighting over the Shrewsbury poisonings and the long-running disputes over antisemitism. As such, of the 100,000 Tory members who returned their ballots on an 80% turnout they narrowly, and comedically, went for May over Gove by 52% to 48%. The significance of the ratio was not lost on anyone.

May enjoyed a brief honeymoon, and shored up Tory fortunes in the polls by winning back floating support from UKIP and Labour. However, she was conscious of her slim inherited majority and the tight margin of her victory. Her speeches intoned on the one nation theme, which seemed to suggest she was determined to put pay to the party squabbling over Europe once and for all. But inevitably, when faced with the other heads of government at Commission meetings she was not seen to be pushing right wing peccadilloes enough. Her promises to act tough came to nought, because there was nothing to act tough about. No bail outs for southern EU states, no Turkey accession, no new agreements necessary for the transfer of more powers. She started to find even the zone of non-punishment was punishing, and when she did try to contrive rows on the approval of the EU budget the press, Farage, and increasingly her backbenchers took her to task. In time, the infighting returned and the poll recovery was slipping. If she was mulling over an early election, by the time of the Spring budget - delivered by the newly promoted Philip Hammond - there was little he said or promised that would make a contest much of a go-er. And so when the EU elections swung by, the Tories fell to third place. The Leave movement found its feet again and returned UKIP as the largest party, with Labour coming a close second. It was unclear if the government would last the distance until May 2020.

Except May 2020 did not happen. Wounded by the awful losses in the EU elections, though not quite as bad as those sustained by John Major in 1994, throughout the Summer and Autumn Leave took to the streets in increasing numbers, culminating in a 100,000-strong march through London that October. The idea the government cheated in 2016 increasingly took on the form of a conspiracy theory, drawing together the liberal elite, collusion between Brussels and "shadowy financiers" (usually, but not exclusively George Soros and the Rothschilds), and evil teachers/lecturers filling younger generations' heads with internationalist rubbish. As the temperature rose because May elected to ignore the movement, some took to camping outside Parliament with sound systems, UKIP banners, and garish Union Jack suits. Questions were raised in the house following the public abuse of Tory remainer MP Anna Soubry while she tried entering the parliamentary estate. On the left, despite May's promises there was little evidence of helping out the poor in Hammond's statements. Osborne's deficit targets are long discarded, but it seems the precarious state of her party and wishing not to give any recalcitrant backbencher an excuse to jump ship and join Farage, as per Douglas Carswell and Mark Reckless in 2014, stayed any reform mindedness she may have had. As a result, when the din from Labour internal warfare died down, as it did for short lulls, there was polling evidence the party was seen more in tune with the sentiments of the British people.

And then Coronavirus happened and up ended politics. May's initial response was widely praised. She entered lockdown when the scientists recommended it, although there were loud complaints about the cancellation of Cheltenham and football fixtures, but the initial three-month quarantine period ensured UK deaths stayed below the hardest hit countries in the EU, like Spain, Italy, and France. But once lockdown was over and everything opened up again, stories came to light of PPE procurement scandals - stories that have not gone away. Farage, before jumping on an anti-face mask bandwagon, temporarily made hay over "careful Britain" handing over cash to states in southern Europe who had not taken the pandemic "seriously". Meanwhile, the furlough scheme offered by Hammond was very obviously influenced by the pressure Labour were applying, but then the chancellor showed a stubborn resistance to extending it and making sure its coverage was as comprehensive as it should have been.

Under the impact of a national crisis, any government's polling figures are going to go up. And May's duly did, reaching a high of eight points in mid-April. But since they've been falling. Labour have regained ground thanks to those losing out and angry at the mismanagement they see, and UKIP are regularly at around 20% as it adds Covid-scepticism and a toddler-like tantrum over tier restrictions and the second lockdown to its populist repertoire.

With all elections postponed until May 2021, by which time most people will have received a vaccination, it looks like May's Tories are in for a very difficult time. In 2016 David Cameron opened a wound to scratch an itch, and the politics flowing from that event have festered. And no amount of telling Leave they lost, the people had spoken and so they should get over it works. Britain is polarised, albeit with the right seemingly helplessly split. Can Labour take advantage and put Jeremy Corbyn into Number 10 next May? It's highly likely - unless May goes to the country promising a second in/out referendum. That might see off UKIP and cohere a block of voters behind the Tories, but poll after poll shows the public are fed up of hearing about Europe. But if making such a rash promise means preventing themselves from getting wiped out, Theresa May will certainly do it.

If we're just going to end up with a no-deal Brexit under a Tory government, we could have had that 4 years ago.

ReplyDeleteHonestly, one of the worst immediate effects of Brexit is how it has derailed and diverted attention from everything else.

Brilliant!

ReplyDeleteNice bit of counter factualism. But yiu don't tell us how the camelhair coated one would have dealt with becoming a honorary Stokie ?

ReplyDeleteGiven that "Boris backed Remain" seems to be the point of divergence in this particular alternate history, it suggests that his actual decision to back Leave was the correct one both for himself and for the interests which the Conservative Party represents (if not for Britain as a whole)...

ReplyDelete