Does Brexit offer the British Left a great opportunity to break free from the restrictions which come with membership of the EU? Is this the chance for a 'Lexit', a moment for Britain to embark on its own independent journey to socialism?

Significant elements on the British Left have been highly critical of European integration ever since the establishment of Common Market or European Economic Community (EEC) following the 1958 Treaty of Rome. The key criticism was made by Nye Bevan, who argued that it rejected socialism and democracy in favour of free trade: "disenfranchisement of the people and ... enfranchisement of market forces". This critique remained powerful within the Labour Movement and was deployed by those arguing for the leave option during the 1975 referendum on British membership of the EEC.

The 1975 referendum result was a victory for those wanting Britain to remain in the EEC but the Left of the Labour Party continued to oppose membership of what became the European Community and then the European Union, arguing that it was incompatible with the imperative requirement of State-led industrial modernization. However, it was a marginalized political force after the 1987 General Election defeat. The locus of the anti-European cause now switched to the Right of the political spectrum. It gained an increasingly strong position within the Tory Party, provoking serious splits which contributed to the humiliating defeat of 1997.

The ongoing turmoil in the Conservatives led David Cameron to call the 2016 referendum on British membership of the EU. We all know what followed: a narrow popular endorsement of withdrawal which so far neither Theresa May's nor Boris Johnson's administrations have been able to deliver. The Conservatives have continued to quarrel over the issue of Brexit. But this has also been a problem for Labour, where there remain voices calling for the people's will to be respected and for the UK to depart from the EU as soon as possible. This group includes Labour MPs with constituencies in Leave voting areas as well as those committed to the view that the EU is an insuperable obstacle to democratic socialism and to the modernization of British industry.

There is no doubt that the EU provides some good material for the socialist critique. Armed by the texts of the Maastricht and Lisbon Treaties (1992 and 2007) the European Commission has consistently played down the idea of 'social Europe' and promoted the liberalisation of services, greater competition and a shift to 'flexible' labour practices (in other words an increase in exploitation) across the EU. Side by side with this has come pressure for the governments of member states to cut spending and balance their budgets, a function of the Stability and Growth Pact (1999) and of the requirements which come with belonging to the Euro group. The countries whose financial systems were most damaged by the 2007-8 Crash have all experienced demands for economies in public spending but it has been Greece where this pressure has been at its most intense. The radical Syriza government, elected in 2015 to take Greece out of the austerity imposed on it by the EU's 'rescue' of its banking network saw its manifesto trashed and the whole nation taken to the edge of social, economic and political breakdown.

This is, however, by no means the whole picture. Across the EU recent years have seen both divergence from and growing resistance to the free market agenda of the Commission. Notable examples can be found in France, Germany and Italy. These countries have all defied the Stability and Growth Pact's 3 per cent deficit requirement regarding government budgets. There are numerous instances of action by national governments to address urgent issues. The French State is committed to a renewables budget of 71 billion Euros between 2019 and 2028, representing a 60 per cent increase in spending under this heading. In the industrial sector it has successfully intervened to prevent General Electric shutting down the plant at Belfort, commissioning in late 2016 15 fast trains at a cost of 630 million Euros. This year the French and German governments agreed a 1.7 billion Euro plan to boost electric vehicle battery production, an initiative seen in Paris and Berlin as both environmentally virtuous and liable to strengthen the countries' automotive sectors against Asian competitors.

Contrary to the assumption of Lexiteers, the nation-state remains strong in the EU. Member governments follow developmental strategies which they deem to be in their own nation's interest and are willing and able to use countervailing force against the Commission's efforts to promote a liberal model of European economic integration. The Maastricht and Lisbon Treaties indicate one route for the EU but some of its most powerful States are marching in the opposite direction. Of course, Brussels may at some point seek to resolve this contradiction in a way favourable to the Commission's version of the European idea. But it has a rather poor record of winning showdowns against a resistance led by Germany, France and Italy. How many would fancy its chances of victory in the future?

A sound Left wing politics is always rooted in things as they actually are but the world of the Lexiteers is not, whether they are discussing the EU or the UK. 40 years ago manufacturing accounted for 30 per cent of the UK's gross national output. Given that it represented so large a fragment of British capital it is hardly surprising that governments made its modernization and ability to out-perform its competitors in Europe and the USA an economic policy priority. The Left's argument that a strategy designed to achieve this would work better if Britain were outside the EEC and able to protect its industrial base and plan its economy without fear of interference and veto from Brussels, was plausible. The Thatcher years (1979-90) saw State intervention largely abandoned in favour of a market-based approach which led to the run-down of whole industries and the closure of many firms. Subsequent administrations, of both major parties, have not deviated from this strategy, so that manufacturing now accounts for not much more than 10 per cent of the GDP: industrial reconstruction and renewal has ceased to be a policy priority for Governments.

While it is true that a State-led industrial strategy has returned to favour in the Labour Party under Jeremy Corbyn's leadership there has been no rehabilitation of the idea that departure from the EU is necessary for this to work. How could there be, given that the EU accounts for 48 per cent of Britain's goods exports and eight per cent of GDP? Departure from the EU without a deal will lead to trade with it on World Trade Organization terms. This means that tariffs will be imposed on goods coming in and going out. It is hard to see how the regeneration of British industry could be achieved by depriving it of free access to European markets and disrupting the supply chains of leading manufacturing corporations. A Labour Government will offer the electorate another referendum on leaving the EU: but the choice will be between remaining and Brexit based on an agreement with Brussels which provides access to the single European market or at least membership of the customs union - which is what the old EEC the Left wanted to leave all those years ago really was. Within contemporary Britain there is neither the political nor the economic basis for a Lexit of the kind favoured by the old Left.

And this takes us to the final point. Lexit may be a will o' the wisp, but a right wing Brexit, a 'Rexit', most certainly is not. The Conservative Party, which had taken Britain into the EEC in 1973, became dominated by Brexiteers. How did this occur? Andrew Gamble's The Conservative Nation (Routledge, 1974 and 2014) is the best guide. Gamble points out that the Tories have historically represented the interests of British capital: for them, the 'politics of power' has been about forming governments committed to the defence of capital and the free enterprise system. To this end, the Party has always cultivated a 'politics of support' designed to attract enough voters for it to win elections. This has traditionally revolved around patriotism and defence of the national interest abroad, (including, if necessary, unilateral resort to the use of force, as in the case of the Falklands War) and determination to protect the British 'way of life'. During and after the Thatcher era the wealth and political influence of the City of London grew even as industry contracted. The shift of power was a function of the nation's switch to a neoliberal political economy. The deregulation associated with the process facilitated freedom of capital on a global basis. Mobile international money flooded into London, much of it handled by hedge funds, which seek to make profits by speculating with borrowed capital. The City of London quickly became the world's number two destination of choice (after Wall Street) for these. By 2019 hedge funds in the City were handling £500 billion, equivalent to 25 per cent of Britain's GDP. Both the scale of business conducted by and the global reach of the City has left finance with a level of influence within the British State it has not enjoyed since before 1914.

Given the transformation of British capitalism since 1979 the politics of power centres on the reproduction of the neoliberal order within the UK and beyond. This, in turn, requires Britain to have an external strategy designed to facilitate its ability to supply ‘business, technology and financial services to emerging markets such as China and India', become 'financial manager of the world' (Paul Mason, 'Britain's Impossible Futures', Le Monde Diplomatique, February 2019). Membership of the EU is not essential to this. The politics of power therefore looks to a British breakout from the EU in order to pursue a global mission, backed by a politics of support which invokes the Conservative Party's core values, rooted in patriotism and determination to protect British culture and 'character' from alien influences such as the EU and mass immigration. Promoted through the press and TV by billionaire Tory-supporting media proprietors with world-wide interests such as Rupert Murdoch, Viscount Rothermere and the Barclay Brothers, this nationalist discourse has sustained a series of Conservative governments since 2010 and achieved its most spectacular success in the 2016 referendum.

The economics and politics of Brexit are therefore Right Wing, fusing neoliberalism and xenophobia. Brexit represents an attempt to recreate the era when London was banker to the world and Elgar and Kipling were heroes of popular culture. This is, without doubt, a doomed and forlorn project. But it is driven by powerful interests located in the old financial heart of British capital. Lexit has no comparable roots in the modern British political economy and no comparable following in modern British popular politics. It is, to use a fashionable term, 'a unicorn'. Rexit, not Lexit, is the only Brexit there is.

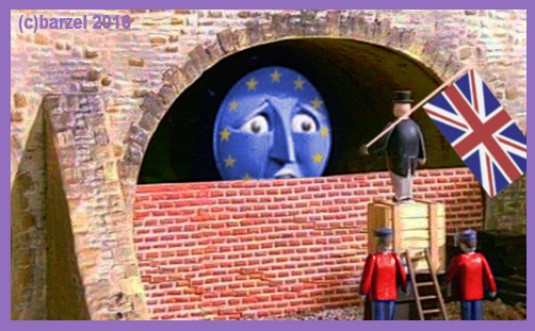

Image Credit

«supply ‘business, technology and financial services to emerging markets such as China and India', become 'financial manager of the world' (Paul Mason, 'Britain's Impossible Futures', Le Monde Diplomatique, February 2019).»

ReplyDeleteThat is what I call the "headquarterization" delusion, that England (or rather southern England or rather the M25 area) can be the headquarters of the world, with all the good high value headquarters jobs (research, accounting, marketing, ...) while the gullible simpletons of China and India get all the low paid factory jobs, and send the big profits to headquarters in London, just it happened first in the English Empire, and then within the UK itself.

That is not going to happen: the chinese and indians are not gullible simpletons, and they have already Shanghai and Mumbai, sophisticated headquarters cities with business, technology and financial services as advanced as any in the M25 area

«an attempt to recreate the era when London was banker to the world»

Rather banker to the English Empire, because London there had a "home" advantage enforced by the gunboats and the redjackets. Headquarters cities need to be at the centre of an empire they rule in order to build a mass of captive markets and guaranteed profits with which they can out-compete those without.

The reality which is well known to B Johnson and the other elite exiters is that the M25 area does not have any "business, technology and financial" advantage over Shanghai or Mumbai, but it can rent for a fee the shield of "sovereignty" to shady spivs across the world to hide their dirtier businesses, much as Switzerland, Singapore, Bermuda, Dubai already do. Unfortunately that type of businesses cannot generate enough income to support a country the size of England, and thus the medium term plan is to dump the south-east overboard, as the north etc. was 30-40 years ago, and concentrate all the opportunities for leasing of "sovereignty" in the M25 area.

And that's why the maniacal insistence of exiters on "sovereignty" not being pooled and on "never surrender to the ECJ".

How about noxit

ReplyDeleteBlissex, what gives the Leave voter coalition such cohesion, given that it seems to contain subgroups with diametrically-opposed interests?

ReplyDeleteFor example, you mention how a "headquarterization" delusion animates a lot of the upper-middle-class Brexiteers, but didn't a lot of working-class people in left-behind towns vote Leave in part as a protest against headquarterization, against a system which forced their offspring to move to London (or at least to a big metropolitan area) if they wanted something better than low-paid insecure work?

And while Empire may have had some impact on wealthy Brexiteers (insofar as a lot of them live off wealth inherited from imperialist ancestors, and therefore for them personally the Empire never really fell), I doubt that this had any influence on working-class Leave voters either...