Video games are interesting in this respect. As the newest media staple in a long line of media staples made possible by the printing press, electricity, and computing what constitutes a canonical video game is open to contestation to some degree. For one, they haven't been around long enough for canonisation to be sanctified by a caste of academic types with research interests in video games. Canons, as such as they are, have been established primarily by games magazines and these are challenged and sniped at by tens of thousands of YouTubers and Twitch'ers. Also complicating matters is that each machine - past and present - has its contested canon, and the invisible hand of the market has built huge followings around a relatively small number of game franchises. Nintendo, of course, rule the roost with largest number of best-selling series, but all top software houses have to have one to a handful mega-sellers to keep them a going concern.

Yet winding the clock back 25 years, it was a little simpler. Not just because the games industry was younger, the technology simpler, and was considered more of a niche hobby for kids and geeks. But because of amusement arcades. These were the big deal. I can remember going into my first arcade - before I'd set eyes on a computer - when I was about five or six and being utterly enthralled by the flashes and the bleepers. Yours truly was far from alone. All throughout the 80s and 90s, they exercised a pull on a generation of young 'uns to the extent that arcades were to gaming what cinema was to film. Titles were released by coin-op firms which were then converted to the various home computer formats (here in Britain, at least), before later getting recycled as compilation fodder and the two/three quid budget titles. Big titles were sought after by the big software houses because of their money spinning potential. Ocean of Manchester and US Gold (owned by, but not that this was common knowledge, also by Ocean) tended to get the big name licenses from the likes of Taito, Konami, Sega, and Capcom, and their conversions for all formats were usually eagerly awaited. While there were plenty of original titles about exclusive to home systems, the arcade was the source of the top tier games. If it was a big hit, a game's chances of becoming canon were very good - provided the conversions were top notch.

Come the dawn of the 16-bit Japanese games console, the big selling points of the PC Engine, Sega MegaDrive, and later the Super Nintendo was their ability to bring the arcade experience home. For the fraction of a cost of a coin-op, all were sold on games that were virtually indistinguishable from their arcade parent. Sega proved particularly adept at this producing early on close - not quite perfect - conversions of its own and select Capcom titles. In North America, this enabled Sega to make significant inroads into the aging NES market, which couldn't hope to compete. In Europe, despite being on a rough technological par with established 16-bit computer formats, side-by-side MegaDrive conversions were better executed, more stylish, and played better than the competition. Unsurprisingly, the computer magazines of the day gave out gushing reviews, more or less sacralising each new arcade conversion to come off the boat from Japan. What was established looked routine and tired, so by the time the SNES arrived here in 1992, Sega had already dealt the home micro a killing blow. It also ensured that first slew of games achieved canonical status from the off, and many to this day retain their place in the pantheon.

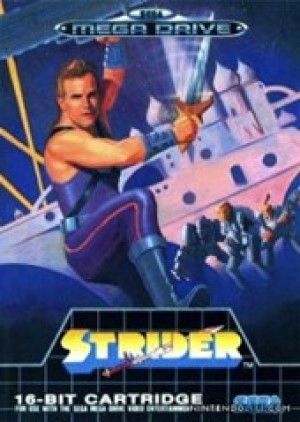

One such title that sold loads of MegaDrives here and in North America was Sega's conversion of Capcom's Strider. Something of a smash in the arcades, it received a warm reception and healthy sales when US Gold handled the home versions here - despite their being not-terribly-close iterations of the original. Nevertheless, it became a must-have title for gamers because it was Strider. The game, which wasn't terribly original, was a stylish platform slash 'em up that cast you as Strider Hiryu, a natty ninja with a nifty blade. The plot, such as it is, has you traipsing through a future Soviet landscape dishing sword-related endings to henchmen, dogs, and robots in ushanka hats. Along the way you acquire power-ups that extend your slashing range, as well as energy bonuses and a couple of drones which, occasionally, turn into a cyborg panther that can be used Shadow Dancer-stylee. And there are your required end-of-level bosses.

MegaDrive Strider wowed because it is a pretty close conversion. Going from the screenshots plastered over contemporary games mags, it looked amazing and attracted superlative comment and scores in the must-have range. And despite retailing for £44.99 on its release (the first eight megabit (just over a megabyte) cartridge) it showed gamers who the future belonged to. Almost from the go it took up a seat in the MegaDrive pantheon and has remained there ever since. It regularly appears in YouTube top tens and has plenty of fans nostalgically waxing over it. I have never understood why.

My own previous experience of this canonical work was the Spectrum version. I wasn't taken with it then, nor was I when I finally acquired Sega's Strider 24 years after its release. Looking at it the game does look stunning - arguably even better than the arcade original. Yet once it moves the animation is pants, the sound an overrated cacophonous mess, and the gameplay is as stiff as a board. There is no satisfaction to be had slicing up the enemies and, I'm afraid to say, the controls aren't as responsive as they should be. It's not a hard game, but it is a dull game and one that doesn't merit the praise piled upon it. Of course, as a relatively early title with a modest sized cart - at least compared with what later became standard 16-bit sizes - the animation and so on can be forgiven, but the action isn't my bag. Compared with the contemporaneous Revenge of Shinobi, it pales.

Sacrilegious words where Sega fandom is concerned, but I just can't imagine how anyone could find this anything than other a brief but dull experience. Again, at least as far as I'm concerned, its merit lies not in the game-in-itself but rather the splash it made at the time. Because it looked arcade perfect and played pretty much like it, replicating a much-loved and successful coin-op guaranteed its canonical status. It's just that status doesn't necessarily mean it's any good.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comments are under moderation.