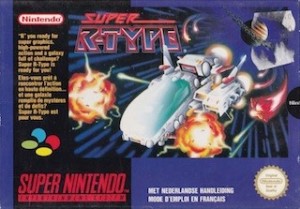

R-Type II made it into the arcades in 1989 and wasn't quite as successful. After all, you can only redefine a genre on so many occasions. By then there were a welter of blasters to compete with that had built on its elder sibling's influence. This time only Commodore's Amiga saw a home port. That was until Nintendo's Super Famicom was released in Japan. To have the biggest name in shooters grace what became the Super Nintendo in the West was a restatement of the company's supremacy. Nintendo may have lost ground in the overseas markets, but it could still rely on having the platform of choice for arcade manufacturers wishing to port their games to home systems. Super R-Type fit this mold perfectly: the biggest name in shoot 'em ups was hitting the biggest name in video games.

Certainly, Super R-Type was very impressive. Converted by IREM themselves, this was hailed as an improvement on the arcade original - a killer accolade for a time when 'arcade perfect' was a much-coveted honour gamers cared about. Small wonder it was a release title when the SNES made it to these shores in Spring 1992: there was a lot of ground it needed to claw back from the MegaDrive's two-year lead. And, on the face of it, Super R-Type is a superlative product. It had all the features of the old game, but benefited from significant upgrades. There were a couple more weapon types you could access, and the huge beam could be powered up twice in succession into a mega-powerful plasma shot that would pretty much obliterate anything. Position yourself at the right position, unleash the beam and even the most fearsome looking boss would crumble. SNES Super R-Type also benefited from an extra level than its arcade counterpart, multiple difficulty levels, and quite a good soundtrack that was redolent of 70s anime like the celebrated Gatchaman. The gameplay was perfectly replicated and, for a brief period, was hailed the best shooter on the system - at least until Capcom's UN Squadron bested it a few months later.

The first time I saw Super R-Type was at the local import gaming emporium, and it looked amazing. The graphics seemed to be carbon copies of the arcade. The action looked frenetic and challenging. But playing it, that was a different matter. There were two chief flaws to this game - one intentional, one not. The first, which is persistently annoying, are the checkpoints or lack thereof. Suppose you battle your way through a tough level only to be smited by the boss at the end, you respawn back at the level's midpoint. That was definitely not cool but a long-established convention whereby difficulty or similar artificial challenges were deliberately deployed by designers to lengthen a game's longevity when, for reasons of technology and memory, there wasn't that much game to play through. The second are the game's technical issues: it is notorious for suffering from slowdown. As an early release, IREM clearly hadn't yet got a handle on the hardware and how to use clever programming to compensate for an almost laughably slow processor. This was all good ammo for the console wars of the time, but the slowdown almost made for a broken game. While it can be used to the player's advantage, such as slowly crawling around a bullet-filled screen, it can be a frightful foe too. Shoot too many opponents and the action ramps up to normal speed, which can see your ship become acquainted with a bullet or the scenery. There must have been hundreds of thousands of SNES owners whose progress through the game was delayed because they fell foul of dodgy programming.

Approaching this from the vantage point of early 21st century gaming, there are two things the experience of chronic slowdown flags up. It interrupts the flow of the game and disrupts whatever narrative the player has imposed on proceedings. The R-Type universe has concocted a tale about the evil Bydo Empire invading things and being thoroughly disreputable, but for a good chunk of players blasting away at hordes of enemies might have involved reliving Star Wars fantasies or something similar. Slowdown breaks this flow down, forcefully curtailing the suspension of belief that was crucial for the story-lite games of the eight and sixteen bit eras. Secondly, it draws attention to the difference between game cultures then and now. These days when a broken game is released, such as Batman: Arkham Knight and Assassin's Creed Unity, developers and publishers are panned, patches have to be rush-released, and gamers return games to the retailer by the bucket load. Back in 1991-2, there was no such culture. Had I been flush enough to have acquired a SNES back then and a copy of Super R-Type, no retailer would have taken it back on the grounds of slowdown. The game wasn't considered broken, it was what it was. As you can see from this contemporaneous review, this issue - which reaches epidemic proportions as the levels wear on - merits but a slight mention in passing. British gamers at least, having been weaned on tape loading and disk-swapping, were habituated to dodgy software, so a bit of on-screen slowdown was nothing.

Super R-Type is an important game because of the place it occupied in the early SNES "must-have" pantheon. For collectors it's perhaps a title no collection should go without. But had I splashed out then on a Super Nintendo and forked out a further £44.99 on this cart (for that was its price upon release), I'm sure disappointment would have set in pretty quickly - especially in comparison to the nifty MegaDrive shooters I was used to.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Comments are under moderation.