Those of you who've been through far left organisations, which is a good chunk of this blog's readership, know that the tradition from which we hail doesn't take elections particularly seriously. The lowest form of class struggle, as I think Lenin put it. At best it's an occasion for making propaganda, as per his latter day disciples, at worst a distraction from the serious business of revolutionary politics. Anarchist traditions, notwithstanding Class War's dalliance with electoral politics, reject voting outright. Underlying both stances is an analysis positioning the state as an instrument of class rule. Taking his queue from Engels, Lenin and most Marxists ever since view it as "bodies of armed men". That is regardless of the appearance a state assumes, their essence remains the same. Britain, Russia, and Egypt for instance have different political systems, different histories of democracy and mass opposition, and range along a scale from relatively liberal to dictatorial. Yet, despite these differences, those states in the final analysis exist to preserve private property, the social relations on which capital depends. There are plenty of establishment politicians and commentators who have been and are genuinely appalled at the brutality of Putin's and Sisi's governments, but were less so when police invaded miners' homes to give them beatings, ran undercover operations on direct actionists, and connived with businesses to blacklist hundreds of trade unionists. Democracy is so much window dressing.

Or is it?

Rosa Luxemburg penned the classic tract against parliamentary socialism, arguing this course of action by the revisionist socialists of her day was not just naive, because they took the slow democratisation of states for their substance, not their ephemera; but also they set themselves up necessarily as managers of capitalism, setting themselves at odds with the movement they came from. For 'reformists', be they social democrats or Labourists, the argument goes that they see the state as something that is essentially neutral. If classes exist, and by no means all in the centre left accept the political salience of class, then the state arbitrates between them. If they are not relevant, the state is a means for securing certain policy outcomes consistent with social justice. At least that is the formal stall set out today. For Luxemburg, social democracy was the view that socialism could be legislated for peacefully through parliaments. That the state is something more than committee rooms and chamber debates was aptly demonstrated by her own murder at the hands of state-sanctioned paramilitaries, a state that had a Social Democrat government.

The truth, in my opinion, lies somewhere between these positions. To use the old language, the state is - confusingly and simultaneously - an instrument and object of class struggle. It is, thanks to the plenty of brutal examples furnished us by history as well as the few touched on here, an instrument for forcibly subsuming living labour - proletarians, workers, whatever you want to call them - under the dominance of dead, congealed labour: capital, business. This, however, is where the classical Marxism from Lenin and Luxemburg, through to Trotskyism, ends. State power and its ultimate abolition is conceived as the objective of revolutionary struggle, but that is it. However, using the same schema, when you have the two main parties contesting an election who map respectively onto the labour movement and the main representatives of capital, what is that if not an example of class struggle? Their objectives too are state power, to use the machinery of government to pursue the interests of the constituencies they represent as articulated, however badly, by their programmes. There is room for this within the present institutional set up. The barriers to a radical reform agenda and the depth to which it can penetrate, for instance, is not based on an ideal typical understanding of the state but always and everywhere conditioned by the balance of forces.

And this brings me to the right and their relationship to the state. The far left take it for granted that the state is arrayed against them but also, in many ways, so do the right. I'm not talking about the racists and the fascists that exercised the Ministry of Sound, but mainstream Conservatism. It would have you think that Nineteen Eighty-Four themed totalitarianism is a heartbeat away. The EU is a Stalinist monolith bent on collectivising Britain's agriculture. The agencies of the state themselves always threaten to subsume plucky entrepreneurs with taxes and red tape. And it's standard now for them to favour a smaller state, one in which the provision of public services are pared back and privatised, where business accountability to the state via laws and regulations are culled though, of course, it's rare that what Althusser called the repressive state apparatus, those bodies of armed men, come in for similar attention. So far, so staple. But consider the desperation of the Tories during the short campaign, even to the extent of talking up their own very British coup. We know from received revolutionary wisdom that the state is on their side, so why are they pulling out all the stops to keep the Tories in power when the programme Labour has put forward hardly drips with deepest red? Is it simply because they're stupid?

No. Another element of the Marxist theory of the state can help us understand what's going on. In the Communist Manifesto, Marx notes that the state is a general committee for managing the common affairs of the bourgeoisie. The owners of big capital as a whole do not exercise political power directly to complement their economic power, it is delegated to their representatives who are organised in parties that strive in part or in whole to condense and articulate those interests. This is because capital, as it competes with one another, tend to be driven by the short-term goals this necessarily engenders. Without politics negotiating and tying together a common will, their general interests - chiefly the security of private property, the persistence of markets, the inviolability of wage labour - might be threatened by coordinated action by labour movements.

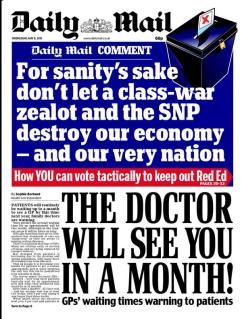

Of course, no one is suggesting that Ed Miliband is going to scoop capitalism into the chamberpot of history, regardless of what the Daily Mail might say. Rather, what is at stake is a rather narrow range of interests within capital itself. Here's the story. New Labour, for all its faults, nevertheless broke the Tory Party's raison d'etre as the go-to political vehicle for big capital and small business. A chunk of the former have drifted back, especially as Labour puts distance between 2015 and 2010 (and 1997), but their monopoly is finished. However, while New Labour basked in widespread support from industry and financial alchemy, the Tories increasingly concentrated the politics of a much narrower range of capital. It benefited from the neoliberal settlement that Blair and Brown maintained, but were also a peculiar mix of the superficially dynamic but socially useless (hello speculators and hedge fund managers), and the most uncompetitive and/or labour intensive. They're not fussed about the long-term. They're not fussed about investment in education, skills, and genuinely useful infrastructure. Lo and behold, the Tories come to power with a little help from their yellow friends and push policies counterproductive from the standpoint of capital-in-general.

Labour doesn't represent a break with capital, far from it. Yet what its current programme does represent is those general interests of capital. A low waged economy with poor levels of investment may suit the immediate interests of Tory backers, but not the commonwealth of business. Ditto for allowing media power to remain in the hands of those allied to sectional, counterproductive interests. Ditto for rent and house building. Ditto for zero hours contracts and insecure work. Ditto for even more brutal cuts to social security. And on it goes. What terrifies the right is that a Labour government will be able to use the machinery of the state to dismantle the hegemony of one - their - section of capital and replace it with another more attuned to the demands of business as a whole. And what really gives them the terrors is that the custodianship of capital's general interests is passing to a party based on the labour movement, one that could, they fear and if driven from below, start making inroads into property, markets, and maybe even wage labour itself.

It's not socialism, but for the Tories and their friends, they know a Labour-directed state could wreck them and their schemes. This is why the election is getting treated as an existential question. And it's why the right generally don't trust state power: it can and might be used against them.

Thanks. Informative and insightful.

ReplyDelete

ReplyDeleteYou had my full attention right up until the paragraph that began:

"The truth, in my opinion, lies somewhere between these positions."