Our third game was conceived in the Orwellian year of 1984 in the dusty backrooms of Moscow's Academy of Sciences. Between the brain of its creator, Alexey Pajitnov, and the Western and Japanese markets where games were big business lay a tortuous path. After mucho shenanigans, court intrigue, and the like, Nintendo secured the rights and packed it in with their newest machine. I am, of course, talking about Tetris, the last game that arguably launched an entire genre of games console: the hand held.

I can still remember its playground debut. The gaming snobs with their PCs, Amigas, Atari STs, and MegaDrives did look down our noses at Nintendo's bland-looking box. A monochrome screen, naff name, and games that cost fifteen to twenty quid? It was like a throwback to a more primitive era instead of marking the dawning of a new one. If it had to be handheld, Atari's ill-fated Lynx and Sega's Game Gear seemed to have the right idea - both offered full colour graphics for starters. And how we larfed when a peripheral-producing firm called Nuby hit the scene. You see, 'Nuby' was a bit like nubby, which was a schoolyard term for crap. Yet for all the opprobrium and snarking the trash talk ceased when a Game Boy got passed around accompanied by Tetris. Whisper it, some of those snobs quietly invested in machines of their own.

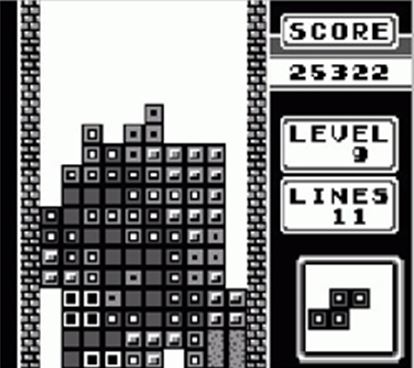

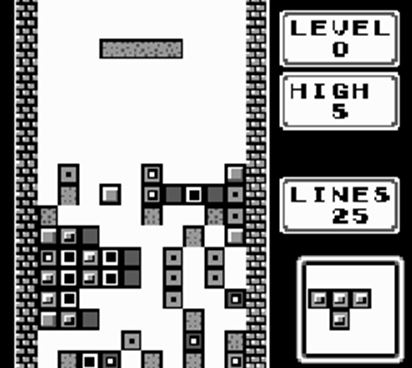

It's not hard to see why. Tetris is an utter monster of a game. I didn't understand what the fuss was about until I took a Game Boy and played the bloody thing. Once you press start and the now familiar playfield comes into view with the irritating yet iconic music (which, forsooth, became a chart hit courtesy of Andrew Lloyd-Webber), the first set of tetrimino blocks float down the screen. You move it around this way and that before settling it at the bottom. Then the next comes and then another. All the time you're manoeuvring and cajoling your blocks into place so one complete line spanning the screen is complete and it disappears. Because that's the challenge if you've spent the last 25 years in a cave. You can complete multiple rows at once for megapoints, but the higher your pile of blocks rise the more likely the game will end. Oh, did I forget to mention that the more lines you put away the faster the rain of teriminos gets? Tetris is a game of pure playability, an utterly absorbing video game pathogen of one-more-turn syndrome. It's simplicity was its demon influence, the hook that lured in far more under-age kids than illicit drinking ever did. I haven't played it for years, but just writing about it makes me want to dig my aged Game Boy out and take the cart for a spin. Tetris taught the console-buying public and game manufacturers an important lesson, which has to be relearned time and again. What matters ultimately is not flashy graphics and kick ass sound. As nice as they are, good, memorable, classic games have to be utterly compelling to play. If a system has the best games, regardless of how powerful it is it will win out over its competitors. As the Game Boy went on to prove in subsequent years.

First off, Tetris can be read as an analogy of the state the Soviet Union had always been in since its inception. Stay with me. After the Bolshevik Revolution, the ruinous civil war, the reconstruction and organised chaos of the Five Year Plans and collectivisation of agriculture, and the do-or-die war with the Nazis, and the ever-present threat of nuclear stand off with the states, the USSR was always a square peg to the round hole of great power relations. What Tetris condenses is the anxiety surrounding the Politburo's ceaseless quest for peaceful co-existence in a US-dominated capitalist world. The random falling of blocks are the ceaseless froth of machinations at the UN, the fickleness of third world allies, opposition at home and in the satellite countries, relations with China. Every line made by the player is an accomplishment that temporarily stabilises the play field, which is immediately challenged again by an appearance of the next block. Unfortunately, it's inevitable that previous false moves raise the level of blocks ever upwards as they start falling faster. The contradictions left unresolved in earlier moves accumulate and conspire to sink you. The game emerged at a conjuncture when that was happening to the USSR, a process that had exploded out into the open by the time kids across the West were slotting Tetris into their Game Boys.

What is interesting about Tetris is its abstraction. You could make the argument that it is the first entirely abstract video game. Consider all that came before it. Nearly all video games before 1984 owed something to practices that existed outside in other media. Pong was abstract table tennis. Breakout involved a bat and ball that demolished bricks. Space Invaders spaceships and aliens. Even Qix (AKA Volfied) dressed itself up in pseudo-science fiction garb. Tetris, based on the manipulation and slotting together of abstract shapes from mathematics, completely eschews the conventions of in-game representation adopted by predecessors and contemporaries. The only concession made are high scores. Aside from that, it is to gaming what Jackson Pollock was to art: there is no reality or logics beyond the game or the work they depended on for meaning - it is entirely self-contained. To get on with Tetris demands you accept its own simple terms of reference and submit to the purity of its play. It's perhaps the nearest a game has ever got to a work of art, and has done so by accentuating its radical specificity as a video game.

A wee exchange between Brother G and me on the Facebook:

ReplyDeleteG: One minor point. You say that Tetris is the first abstract computer game, comparing it to pong which was an abstract representation of a real life game.

Tetris was see on a puzzle game that used the same types of pieces that you needed to fit into a wooden block.

The only innovation was to scroll the blocks once a line was completed.

Me: Not so, nothing like Tetris existed in terms of board games or paper and pencil games. I remember being at school and the only use we had for these shapes was when we had a lesson on tessellating patterns. Blocks, of course, existed. Lego, stickle bricks, etc. were variations on a theme but they were not games with bounded rules. Tetris was and is :)